How to read guitar sheet music

It’s nice to discover new music. You want to immediately pick out the chords, solos, guitar arpeggios, learn all this beauty and repeat it endlessly. But not everyone can figure out a song by ear. Besides, it takes a lot of time to work it out. That’s why musicians need to know how to read guitar sheet music. We read sheet music when we’re learning new exercises to sharpen our technique, when we’re learning to play classics or world-famous hits, and when we’re analyzing beloved songs.

Knowing how to read guitar sheet music is also useful when you’re working in a group. Musicians are used to sharing musical ideas, exchanging tips and helping each other think of melody and harmony ideas. It is even necessary just to avoid forgetting a newly composed line. Then you can return to it, refine it and develop it. See how you can read sheet music and symbols for guitar in different notation formats.

Notation methods

The traditional and universal method for all players is standard musical notation written on the staff. This can be used to record the part of any instrument. Music school and classical school graduates usually have a good grasp of sheet music, or at least know the basics. Reading guitar sheet music and playing it instantly on the fingerboard is a skill that takes years to master. If you’ve only learned to recognize notes and understand durations, it’s already an achievement.

For many guitarists, mastering chords is enough. They don’t need to understand how to read guitar notes in detail. They know which strings to press to get a particular chord. By changing fingerings, they create harmonic sequences and can, for example, accompany themselves while singing. But to do this, you must learn chord symbols and the diagrams that show their fingerings.

And perhaps the most common way for all levels guitarists to read guitar notes is tablature. It can be handled by beginners and professional players alike. It’s a handy and flexible notation. With it, you can convey a harmonic or melodic part in a generalized way, without detail. But for this format, many symbols denote strokes and rhythmic nuances. In this article, we will consider notations and chord notation in all three types, but we will pay special attention to tablature.

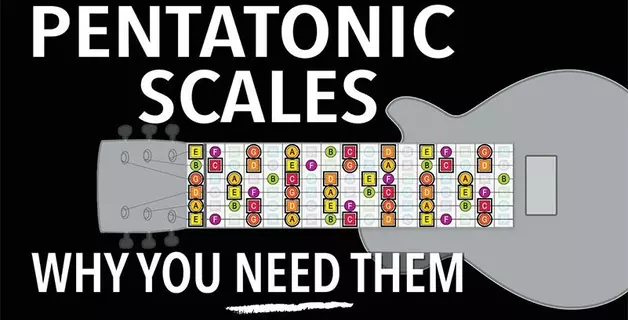

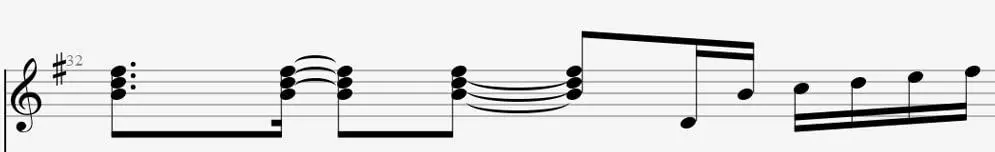

How to read guitar sheet music in classical notation

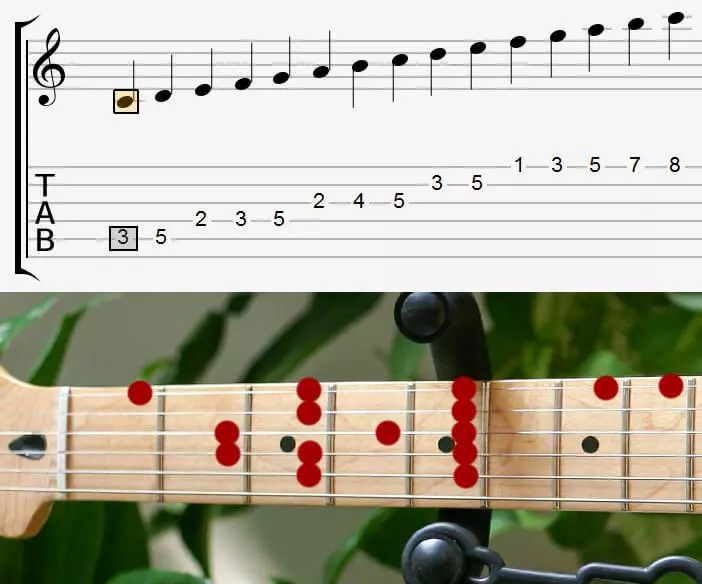

The musical staff is made up of five lines. Notes are shown as noteheads placed on or between the lines. Notes that fall outside the staff are written on ledger lines (for example, middle C in the treble clef). The curled symbol at the beginning is the treble clef. It indicates that the first line is E, the second G, the third B, the fourth D, and the fifth F (the positions differ in the bass clef). Between, below, and above the lines are the notes D, F, A, C, E, G. To read guitar notes, you need to know where they appear on the fretboard. Here they are.

The C major and A minor scales fit naturally on the fretboard. On the piano, the white keys correspond to these notes. To indicate sharps, flats, or notes from other keys, we use sharp and flat symbols, and natural signs cancel previous accidentals. This is enough to get a basic understanding of how to read notes on guitar. Let’s not go deeper into full notation theory here.

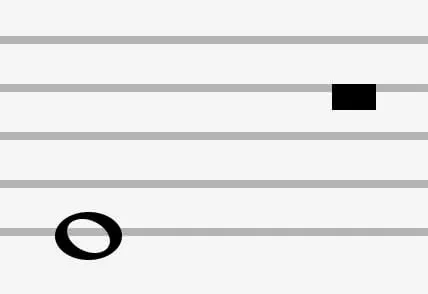

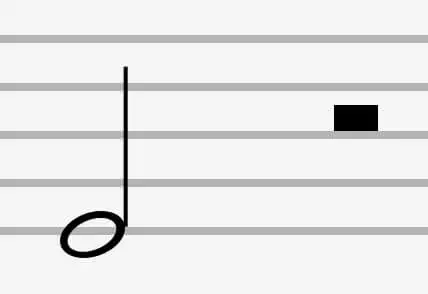

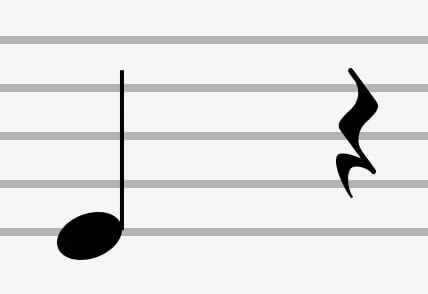

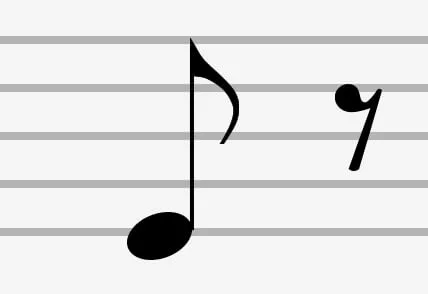

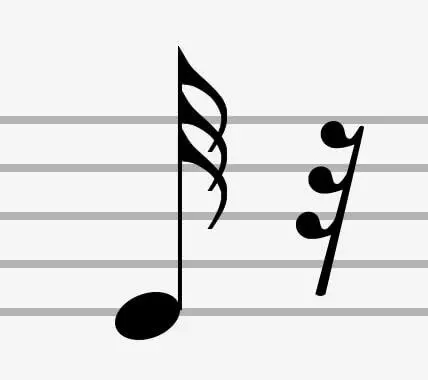

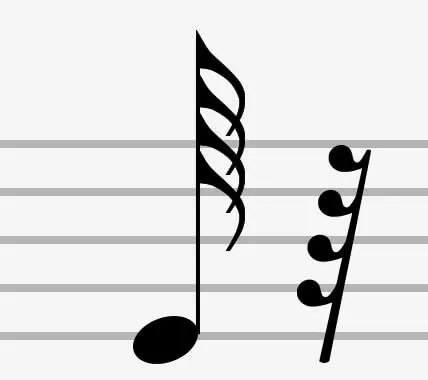

It’s important, however, to have a general idea of rhythm and note durations. Rhythm is harder to read than noteheads. At the beginning of a staff, after the clef, we see the time signature. Most often it’s “4/4” — four quarter-note beats. This means the measure is divided into four quarter notes, counted as “one-two-three-four.” Two half notes or one whole note can fill the measure instead. And we can subdivide it into eighth notes (“one-and-two-and-three-and-four-and”), sixteenth notes, or even smaller values. Rests also come in all these durations. Combining them creates rhythmic patterns. Here’s the full set of note values.

Seems hard? Reading guitar sheet music in classical notation is generally challenging. Understanding durations right away means operating at a reasonably advanced level. But not all musicians need this, so we often use simpler formats instead. There are easier ways to read and write guitar music. Let’s move on to those.

Chords

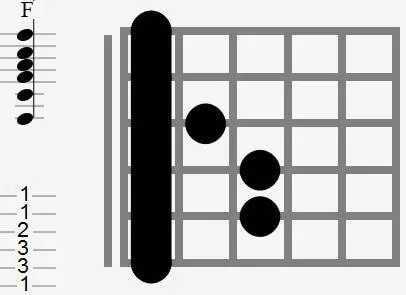

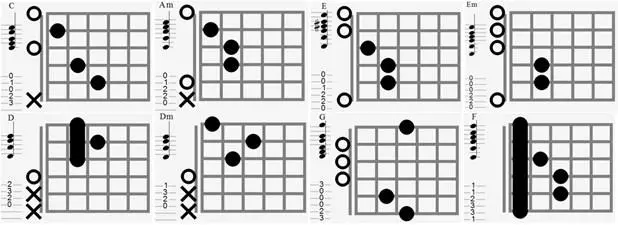

When we play several notes at once, we get chords: triads, seventh chords, sixth chords, ninth chords, and more. Traditionally, they’re written as stacked notes on the staff. But it’s more convenient to assign each chord a letter name and use these symbols universally. This makes reading guitar sheet music much easier. You don’t even need a staff; you can write the chord symbol directly above the lyrics. The most common basic chords are C, Am, E, Em, D, Dm, G, and F.

But you still need to learn how chord diagrams work. The six horizontal lines represent the strings: the lowest-pitched (thickest) at the bottom and the highest-pitched (thinnest) at the top. They’re drawn upside down because this reflects the guitarist’s view when looking down at the fretboard. The vertical lines represent frets. Dots indicate where to press the strings. There are also rotated diagrams where strings are vertical and frets are horizontal. Now you know how to read guitar sheet music using chord symbols and diagrams.

Composers and jazz musicians use an even more flexible method. They read chords according to scale degree and mark them with Roman numerals. For example, in A minor, Am is I, Bdim is II, C is III, Dm is IV, Em is V, F is VI, and G is VII. When musicians need to transpose to a different key, they don’t rewrite the actual chord letters — they transfer the same numbers to the new key. This is another way guitar music is interpreted in the broader musical world.

Tablature

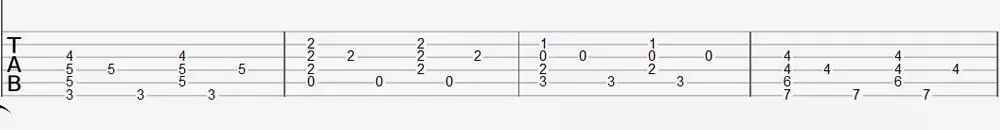

Tabulature came about then classical notation with chord diagrams got combined. This is the most convenient way to write any guitar part, whether chordal or melodic. While standard notation can be used for any instrument, tablature is specifically designed for guitar — and for ukulele, which uses four lines instead of six.

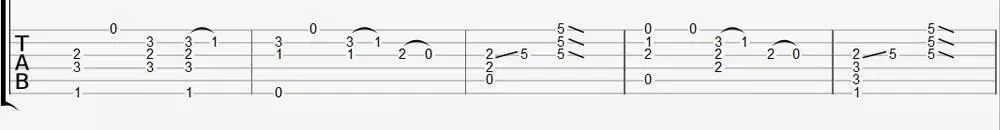

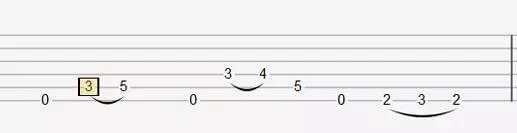

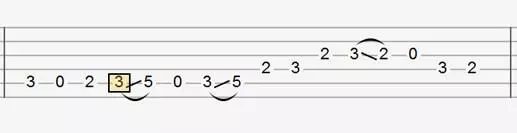

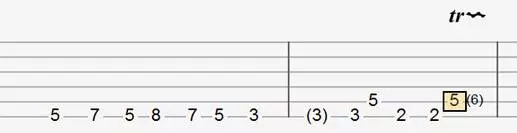

So, how do you read guitar sheet music in tablature? Just like in chord diagrams, the horizontal lines represent the strings: the lowest at the bottom and the highest at the top. The numbers indicate which fret to press. Read from left to right, playing the notes in order. A “0” means to play the open string. The process is straightforward — almost like following a visual game. Here’s an example.

Here the melody is combined with chords. First, we see a three-note chord shape: the left hand presses the strings at the first, third, and second frets. Then we play the open first string and place a similar chord shape on different strings. And so on. Looking at the whole piece, you’ll see that the chords alternate with a single note on the open first string. You just need to understand the shapes and practice your finger coordination. You’ll also notice curved lines and diagonal marks, which we’ll return to shortly.

Reading guitar sheet music this way is very convenient. But this is the basic form of tablature. It contains no rhythmic information at all. If you already know how the piece sounds, you can play it in the correct rhythm. For breaking down a familiar song, this simplified format works well. But to write a new part or mark its rhythm, you’ll need symbols that indicate rhythmic values.

But even this method does not provide us complete information. The extended version of tablature shows how to read guitar notes with expressive detail, making them sound polished, clean, and professional. Good guitarists don’t just play the correct notes — they use many techniques and subtle phrasing nuances. All of this can be written in tablature as well.

Techniques in tabs

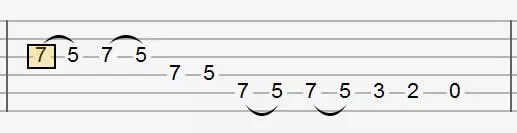

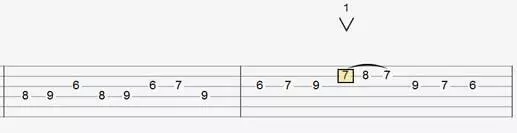

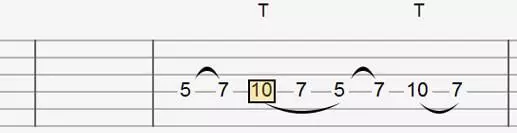

Hammer-on. This technique is also known as ascending legato. When you read guitar sheet music, look for curved lines connecting two numbers. This indicates the notes should be played smoothly without a break. On piano this is done by releasing the first key as the next is pressed. On guitar, the first note has a clear pick attack, while the second note does not.

To play a hammer-on in tablature, strike the first note with the pick and then tap the next fret with a left-hand finger without lifting the first finger. In text form, a hammer-on is marked with “h” or sometimes “^,” as in “5h6” or “5^6.”

Pull-off. This is the opposite direction — descending legato. In text tabs it’s notated with “p” or sometimes “^,” as in “6p5” or “6^5.” A pull-off is also shown with a curved line. You fret two notes, play the higher one with a pick, and then pull your finger off the string so the lower note rings.

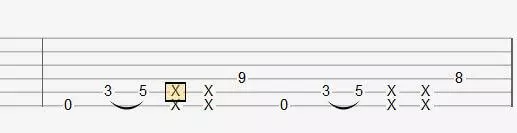

Mute (dead notes). X-shaped noteheads or “x” markings indicate muted notes. Lightly lay your left hand on the string without pressing it and strike it with the pick. The sound produced is percussive and pitchless. These dead notes are used to add rhythmic texture to a solo or to break up sustained melodic lines.

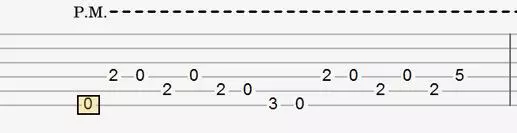

Palm muting. You may also see “pm.” This means Palm Muting, a technique that produces a muted sound in which the pitch is still audible. To play it, fret the note normally and rest the edge of your picking-hand palm lightly on the strings near the bridge while picking.

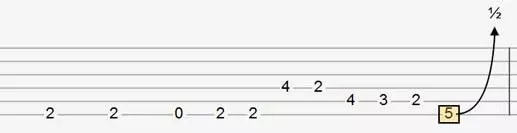

Slide. Slides are shown with a slash (“/”), “sl,” or a straight line between fret numbers. Play the first note with the pick and slide your finger to the second note without lifting it. Slides can move upward or downward.

Bend. In tablature, bends are written with a “b” (for example, “7b9”). Fret the note, strike it, and push the string so the pitch rises to match the target fret. The second number shows the target pitch. Bends may also be shown with curved or angled lines.

Whammy bar technique. Not all guitars have a tremolo (whammy) bar. If the tab uses symbols like “7\5/7,” it means quickly dipping the pitch by pushing the bar and returning it. The number inside the slashes shows how many semitones the pitch is lowered. The technique can also be shown with a “v.”

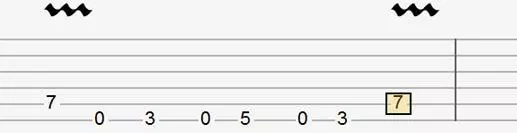

Vibrato. Vibrato is used on almost every sustained guitar note. In tablature, it’s shown with “~.” Fret the note, play it, and gently move your finger up and down to modulate the pitch. The movement should be subtle and rhythmic. A stronger vibrato can be created by slightly sliding the finger along the string.

Trill. A trill is a rapid alternation between two notes, typically played as repeated hammer-ons and pull-offs. It may be marked as “tr” or “tr~~~~.” Trills are used on guitar to create tension and expressive energy before resolving.

Tremolo. When a single number is repeated many times in tablature, the note is played repeatedly. To indicate very fast repetition — sixteenth-notes, thirty-seconds, or sixty-fourths — tabs use “TR.” Sometimes it is followed by “~” to show the approximate length.

Tapping. Tapping extends the hammer-on technique by using a right-hand finger to strike a fret, shown in tabs as “t.” A sequence like “5h7t10p7p5” means hammer-on, tap, and pull-off actions executed by both hands. Tapping increases speed and produces a distinctive sound.

Harmonics. Harmonics create a soft, airy tone. Natural harmonics are shown with angle brackets (“<>”). Lightly touch the string above the metal fret, strike the note, and lift your finger. Natural harmonics occur at the 12th, 7th, and 5th frets. Artificial harmonics can be produced anywhere but require practice.

Practical tips for reading guitar notation

Start by learning chords. Mastering basic chord fingerings is simple. Then practice switching between them. This helps you change chords smoothly without losing the rhythm. Repeating transitions builds muscle memory, and soon your hands will move automatically. Once you master the shapes, you’ll recognize chords quickly in tablature.

Learn to read guitar notes in stages. First, practice locating the fret and string shown by the number. This is easy — the goal is to build speed and accuracy. Next, practice different articulations and techniques. You don’t even need specific tab examples; you can create simple exercises yourself. The third stage is learning rhythms. When you understand rhythm patterns quickly, you’re almost at the top. The only thing left is classical notation.

Practice with real songs. You’ve learned how to read guitar notes, but real learning comes from applying them. Don’t limit yourself to the examples in this article. Take tablature for popular songs, solos, riffs, and bridges, and see how famous tracks are put together. This not only helps you read guitar sheet music — it also reveals the musical logic behind great composers and guitarists.

Use helpful software. Programs like Guitar Pro are made for working with tabs. You can read guitar sheet music written by others or create your own. These programs let you adjust articulations, rhythm, sound, and arrangements, adding other instruments as needed.

Work with sequencers

Some music recording software includes a notation mode. You place notes on a grid while viewing a virtual piano keyboard. The software then converts everything into classical notation. This helps you get comfortable with durations and teaches you how to read guitar notes on the staff.

Conclusion

You’ve learned about chord symbols, looked at alphabetic and numeric notation, and understood how chord diagrams are built. We briefly explored standard classical notation and explained how rhythm is shown. And we covered in detail the most convenient notation method for guitarists — tablature — along with the techniques expressed in it.

Knowing how to read guitar notes isn’t required for everyone. But it helps you learn unfamiliar music faster and understand what’s happening on the fretboard. If you absorb everything in this article, follow the recommendations, and practice the techniques you’ve learned, you’ll raise your guitar skills by several levels. Don’t wait — start now.