Basic music theory

Music is a universal language that conveys emotions. So why do we need music theory?

Music theory is a kind of blueprint for understanding music. Of course, you can feel music intuitively without knowing the theory, but a deep knowledge of the basics helps you become a more conscious and expressive musician. Learning basic theory allows you to better understand the language of music.

This guide will help you master the basics of music theory, whether you are a beginner or have experience. By studying notation, rhythms, scales, chords, keys, and more, you will gain the knowledge you need to express yourself in music and make your compositions more expressive.

Music

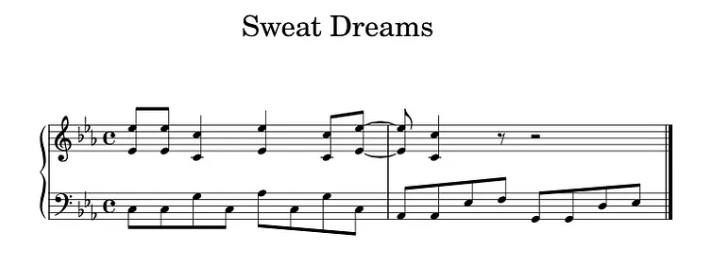

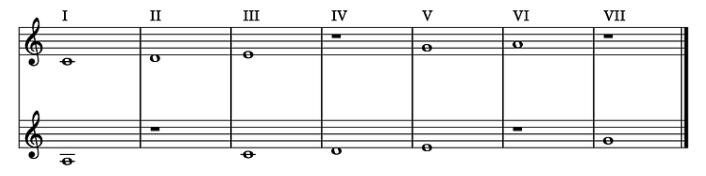

Piano music usually includes a melody and accompaniment.

The melody is usually a single-voice line that can be sung. It is most often written in the treble clef and placed on the upper staff.

The accompaniment supports the melody, consisting of chords and a bass line. It is written in the bass clef on the lower staff.

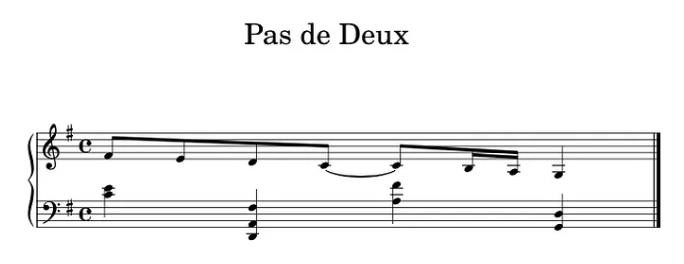

The result is a single-voice melody accompanied by a chordal accompaniment:

Or it could be the other way around. The melody comes from below, and the accompaniment is above:

Music Theory Basics

Music theory creates a universal language for communicating musical ideas, allowing musicians to communicate effectively. By learning these concepts, you can gain a deeper understanding of how music works, become a better listener and creator, and improve your interactions with other musicians.

Who needs music theory

Music theory is useful for anyone who wants to understand music more deeply, regardless of their level of training. You don’t have to be a music professor! Whether you enjoy listening to music at the end of a long week or improvising on the guitar, knowing theory will deepen your perception and enrich your musical experience.

Many self-taught musicians fear that studying theory will deprive them of the ability to play intuitively and intuitively. However, music theory does not limit creativity, but, on the contrary, provides tools that allow you to express your feelings through music more accurately and fully. It helps you create more detailed musical compositions that match your intuitive ideas.

Theory can be studied both in educational institutions and independently, gradually integrating its elements into your creative process.

Beginning of the musical journey

Every piece of music is built on three basic components: melody, harmony and rhythm. These elements help create an intuitive connection with music.

Basics of Music Theory

Melodies, harmonies, and rhythms are made up of the following key elements:

- Scales: a series of half-tones and whole tones that melodies are built on;

- Chords: combinations of notes played simultaneously that create harmony, such as the basic major and minor chords;

- Key: the tonal center of a composition that determines the harmonic foundation and relationships between chords;

- Musical notation: a system of symbols that represents musical sounds, such as pitch and rhythm, in written form.

To create a cohesive sound for a melody and accompaniment, notes from a single key, called a scale, are usually used.

Intervals

An interval is the distance between two notes. The smallest interval is a semitone, on a piano this is the distance between adjacent keys, regardless of their color. Two semitones make a tone.

The entire scale from C to C (or, for example, from A to A) is divided into 12 evenly spaced semitones. The most commonly used intervals are the octave and the third.

Octave: the distance between two notes of the same name, for example, from C to the next C. There are 12 semitones in an octave. Octaves sound especially harmonious in the lower register of the piano.

Physically, an octave is an interval between notes where the frequency of the second note is twice the frequency of the first. For example, the frequency of the note A is 440 Hz, and the next A is 880 Hz.

Third: There are two types of thirds – minor and major. A minor third includes three semitones, and a major third includes four.

Types of intervals

Perfect intervals: include 4 tones, 5 tones, and an octave.

Major intervals: include 2, 3, 6, and 7 tones.

Augmented intervals: are obtained by increasing a perfect interval by a semitone.

Diminished intervals: are obtained by decreasing a perfect interval by a semitone.

Minor intervals: are obtained by decreasing a major interval by a semitone.

Scales

Scale patterns are patterns of pitches that serve as the basis for creating melodies. In music, pitches are represented by notes, and are a specific set of tones and semitones that form the sound of a melody. These patterns give a scale its unique sound and determine its role in a composition.

There are many scales, each with its own unique moods, emotions, and characteristics. The most popular are the major and minor scales: the major scale sounds happy, and the minor scale sounds sad. The main difference between them is the third note of the scale, where in the major scale it is a tone higher than the second note, and in the minor scale it is a semitone higher. In Western music, it is the third note of the scale that is key, as it determines the overall mood and character of the sound.

There are other scales, each with its own unique melodic structure. For example, the pentatonic scale and its more complex version, the blues scale, as well as the chromatic scale and many others.

Knowing scales and chords plays an important role in creating music, as they form the sound foundation of a piece. Mastering different scales can open up new creative possibilities and improve your skills as a composer.

Chords

Chords are combinations of several notes played at the same time and are the basis of harmony in music. A chord is usually made up of three or more notes. A three-note chord is called a triad. The same principles used to create scales apply to chords, defining the steps between notes, known as intervals.

There are four basic types of chords:

- Major chord: Has a happy and bright sound, consisting of the root, major third, and perfect fifth;

- Minor chord: Has a sad and melancholy sound, consisting of the root, minor third, and perfect fifth;

- Diminished chord: Has a tense and unstable sound, consisting of the root, minor third, and diminished fifth;

- Augmented chord: Has a dramatic and mysterious feel, consisting of the root, major third, and augmented fifth.

Chords can combine major and minor triads, as well as inversions that change the order of notes within a chord. Learning different chords and their combinations can help define the unique character of a song. For example, changing the structure of the main major triad (1-3-5) and moving the fifth note down can create a completely new emotional coloring of the chord. The basis of songwriting is the chord progression, which is a sequence of chords. As you develop your skills in chord arrangement, you will be able to create more complex and rich music. Understanding the structure of chords – from basic forms to more complex variations – will open up new horizons in your music creation.

Triad Inversions

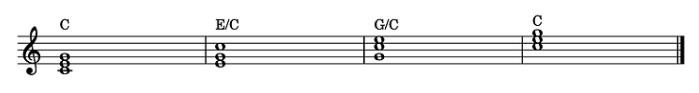

Triads can be inverted to create different inversions, which adds variety to performance and makes the instrument easier to play. Proper use of chord inversions minimizes movement between keys, allowing for smooth performance. To create a chord inversion, move the bottom note of the chord up an octave. Take the C major chord, for example.

Each triad has two possible inversions. If we continue to invert the chord, we get the same chord, only an octave higher. The first inversion of a triad is called a sixth chord, and the second is a fourth-sixth chord. In educational materials, they are often simply called the first and second inversions. In musical notation, inverted chords are indicated by indicating the bass note. For example, for a C major (C) chord, the first inversion with the low note E is indicated as E/C, and the second inversion with the low note G is indicated as G/C.

How to distinguish the first inversion from the second

You can distinguish the first inversion from the second by intervals. The first inversion includes a minor third (3 semitones) and a fourth (5 semitones), that is, the distance from the middle to the top note in the chord is greater. The second inversion contains a fourth and a major third (4 semitones), with a greater distance from the bottom note to the middle than from the middle to the top.

Root note position of a chord

The root note of a chord, called the tonic, is in different positions depending on the inversion. In a triad, the root note is first, for example, in a C major (C) chord, it is the note C. In first inversion, the root note is moved up an octave and is last, for example, E, G, C. In second inversion, the root note is in the middle of the chord, for example, G, C, E.

Transforming a major chord into a minor chord or vice versa

To transform a major triad into a minor one, simply lower the middle note by a semitone. For example, in a C major (C) chord, lowering the E note by a semitone transforms it into a C minor (Cm), which consists of the notes C, Eb, G. The reverse process, transforming a minor triad into a major one, requires raising the middle note by a semitone, for example, D minor (Dm) is transformed into D major (D) by raising the F note by a semitone, which gives the notes D, F#, A. To change the first inversion of a major or minor chord, you need to lower or raise the bottom note, and for the second inversion, you need to lower or raise the top note of the chord

Quinta chord

If you take only the outer notes of a triad, excluding the central one, you get a quinta chord, designated by the number 5, for example, C5.

Suspended chord

In a suspended chord, instead of the central note, a fourth or major second from the lower note is used. Such a chord is designated, for example, as Csus2 or Csus4, if we are talking about C.

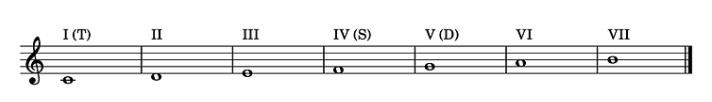

Keys

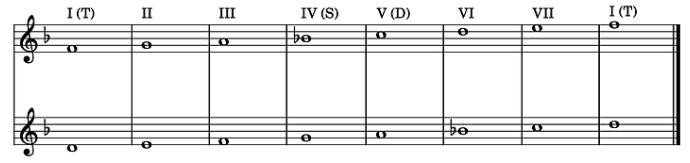

A key is a set of seven degrees (notes) that determine the character of the sound. These degrees are designated by Roman numerals and each of them performs a specific function. Functions are tied to degrees, not to specific notes.

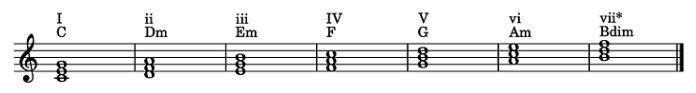

Let’s consider the key of C major:

- Tonic (I, T) – the first step that sets the basic tonality;

- Dominant (V, D) is the fifth degree from the tonic. If the tonic is C, then the dominant is G;

- Subdominant (IV, S) is the fifth degree, counted down from the tonic. If you count up, it will be the fourth degree. In C major, the subdominant is F.

Function inversions

To indicate the inversion of functions, numbers are added to their names.

Stable and unstable sounds.

The tonic triad includes the I, III and V degrees, which are stable. The melody can be completed on them. The remaining degrees are considered unstable and tend to the nearest stable ones, which is called resolution.

Examples of resolution:

- II => I (down)

- IV => III (down)

- VI => V (down)

- VI => I (up, the nearest lower one is also unstable)

Introductory notes and humming

Introductory notes are the notes surrounding the tonic. The tonic’s neighbors above and below are the II and VII degrees, respectively. The VII degree is called the ascending introductory note, and the II degree is called the descending introductory note. Humming involves playing introductory notes around the tonic or other stable notes, such as the III and V degrees.

Examples of humming:

For the I degree — VII and II

For the III degree — II and IV

For the V degree — IV and VI

Parallel and Related Keys

To add variety to music, transitions into parallel and related keys are used, which can be short-term (deviations) or permanent (modulations).

Parallel keys are major and minor keys with the same signs in the key.

Related keys are keys associated with T (tonic), S (subdominant) and D (dominant).

In addition, for a major key, the key of the minor subdominant is considered related, and for a minor key, the key of the major subdominant.

For example, for C major, the related keys are:

- A minor (parallel key, built from T);

- F major and D minor (built from S);

- G major and E minor (built from D);

- F minor (minor subdominant).

Defining a Key

A key is defined by the signs on the key (sharps and flats) and specific notes. These signs can be used to determine parallel keys. You can determine whether a key is major or minor by the notes on which the piece begins and ends.

- Sharps: To determine a major key, look at the last sharp and go up one tone; for a minor key, go down one tone. If the resulting note also has a sharp, then the key has a sharp (for example, if the key has one sharp – F#, this could mean G major or E minor);

- Flats: If the key has one flat, this could be F major or D minor. If there are several flats in the key, focus on the penultimate flat – it indicates a major key (for example, if the penultimate flat is A-flat, then the key is E-flat major). To go from a major key to a parallel minor key, you need to go down 1.5 tones (or three semitones). For example, for C major, the parallel minor key is A minor.

C major and A minor

C major and A minor are parallel keys that have no key signature.

These parallel keys use the same notes and chords. To determine which key, C major or A minor, is used, you need to pay attention to the sequence of chords and their functional meaning. Often, a piece ends on the tonic, which helps determine the key.

In major keys, chords built on the tonic, subdominant, and dominant are major. Chords built on the 2nd, 3rd, and 6th degrees are minor, and those on the 7th degree are diminished.

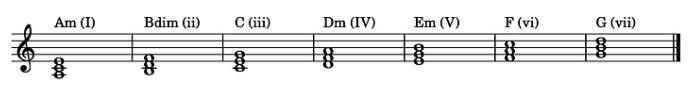

Since parallel keys use the same notes, the chords will also match, just shifted into a different sequence.

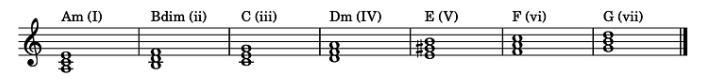

In minor keys, the tonic is often made major, which increases the attraction to it by decreasing the interval between G and A. As a result, the tonic minor chord Em is transformed into a major E, and the other chords remain unchanged.

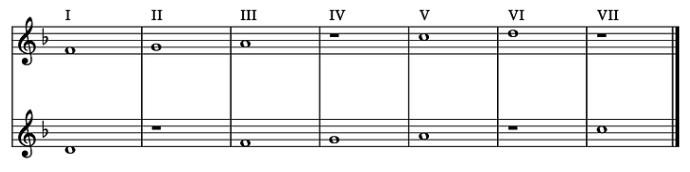

Pentatonic Scale C Major and A Minor

The pentatonic scale is a unique scale that lacks a tonic, dominant, and subdominant. In this scale, all notes are equivalent, making it the same for both major and minor.

This scale is formed by eliminating two notes: in the major scale, the IV and VII degrees are removed, and in the minor scale, the same notes, that is, the II and VI degrees, are removed.

The peculiarity of the pentatonic scale is that it does not create tension and, accordingly, does not require resolution. This allows the melody to begin and end on any note, which makes it ideal for spontaneous improvisation.

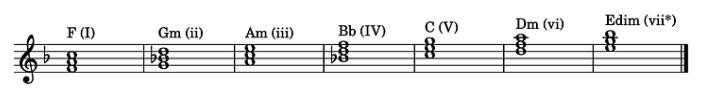

F major and D minor

F major and D minor are parallel keys that have a common key signature – one flat on the note B. These keys are also related to C major. Accidental signs are indicated again for better perception.

Chords of the key of F major:

Chords of the key of F major:

Pentatonic Scale F Major and D Minor

To determine all the notes of the pentatonic scale, you need to play all the black keys on the piano and then lower each of them a semitone to the white keys.

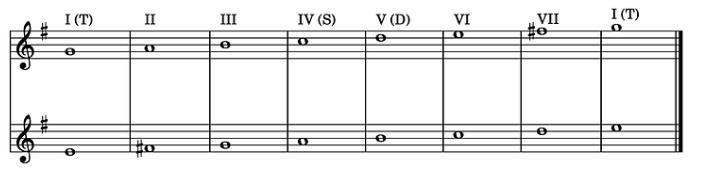

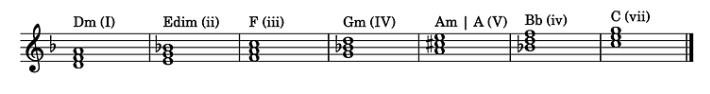

G major and E minor

G major and E minor are parallel keys that share the same F sharp. They are also considered relatives of C major. Accidentals are provided for clarity.

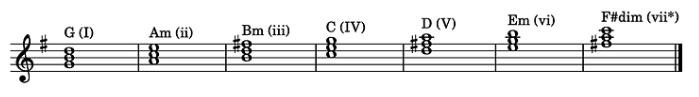

Chords for the key of G major:

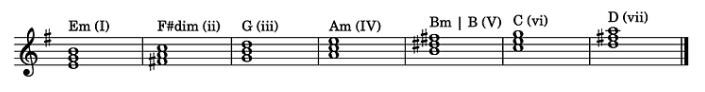

Chords for the key of E minor:

Keys

A musical composition is built on major or minor scales, which form its tonal basis. This set of rules is called the musical key. The key determines which notes and chords will be used in a piece.

A key signature, presented at the beginning of a piece, indicates the presence of sharps (#) or flats (b), which determine the key. A sharp indicates that the note should be played a semitone higher than the standard sound, and a flat indicates a semitone lower. Key signatures help musicians understand the scale structure and harmony of a composition. For convenience, tables are often used to identify key signatures and their corresponding keys.

Sometimes a composition may change its key, which is called modulation. Modulation adds emotional depth and variety to a composition. In modern pop music, modulations are rare, while in video game soundtracks they can occur quite often, creating a dynamic sound space.

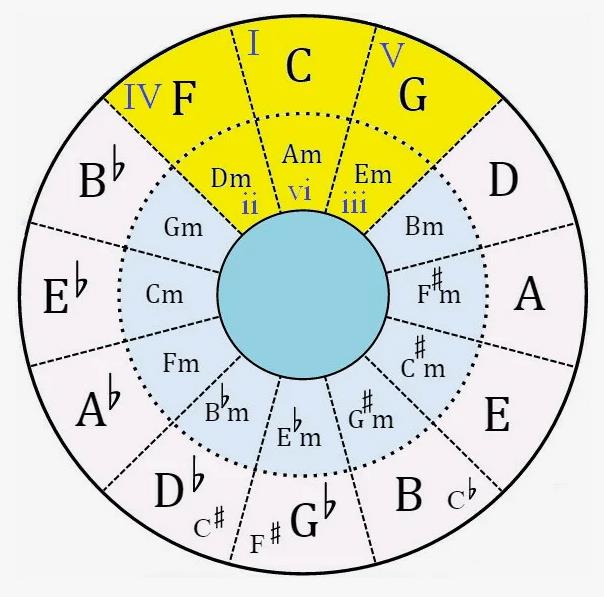

To better understand the relationship between different keys, the circle of fifths is used. This circle visualizes tonal relationships, like the dial of a clock, where each key has its place.

The circle of fifths arranges keys according to the number of sharps or flats, starting with the note C major.

Musical Notation

Musical notation is the written language of music that allows musical ideas to be communicated visually and understood by other musicians.

The basic elements of musical notation are:

- Staff: Consists of five horizontal lines on which musical symbols are placed to indicate the pitch and duration of notes;

- Clefs: Assign specific notes to specific lines on the staff. The most common are the treble clef (for high notes) and the bass clef (for low notes);

- Notes: Indicate the pitch and duration of notes by representing them as symbols on the staff. A note’s position on the lines determines its pitch; the higher a note is on the lines, the higher its pitch. Notes also come in different shapes to indicate rhythm.

These components form the basis on which scales and chords are built in a musical composition. Once you have mastered this “language”, you will be able to read and write music, and fully understand it without listening to it. This improves your understanding of music theory and makes it easier to communicate with other musicians using the universal language of music.

Rhythm

Rhythm, along with chords and scales, is a fundamental element of music. Musical notation includes special symbols and rules for conveying the rhythmic aspects of a composition.

Meter time indicates the number of beats in a measure and the duration of the note that takes up one beat. It is written as a fraction: the top number indicates the number of beats and the bottom number indicates the duration of the note. For example, 4/4 time means four beats in a measure, with each quarter note taking up one beat.

Rhythmic patterns can range from simple to complex, including polyrhythms that create unique rhythms.

Understanding rhythm is also useful in the process of creating music in digital audio workstations (DAWs), where notes are edited in a MIDI editor that maps piano keys. DAWs also allow you to apply swing and other rhythmic adjustments to music.

Elements of Composition

As you learn music, it is important to learn the different elements of composition that make a piece more interesting and expressive. Here are some key concepts to consider:

- Dynamics: Reflects the volume of a performance and affects the intensity and energy of the music. Common notations in sheet music include piano (soft) and forte (loud);

- Articulation: Determines how notes are played, such as staccato (short and staccato) or legato (smooth and connected);

- Form: The overall structure of a piece, such as verse-chorus-verse-chorus form in pop music or sonata form in classical music;

- Texture: The organization of layers of sound or voices in a piece, such as monophonic (single-voice) or polyphonic (multi-voice).

Ear Training

Learning about music theory is just the beginning. The next step is learning to hear and recognize these concepts in real music. Ear training helps you connect theory with practical application. By listening to music, you can improve your ability to recognize intervals, chords, melodies, and rhythms.

When your ear can recognize theory, you can use this knowledge in your compositions and performances. This allows you to approach music creation and performance more intuitively, making theory a natural part of your musical thinking.

Summary

Once you understand the basics of music theory and learn to hear these concepts, you can apply them to your own projects. Whether you’re improvising with a band, writing music, or creating tracks in a digital audio workstation (DAW), understanding theory will help you create better, more engaging pieces. These basic elements are the foundation of all genres of music, from the complex structures of classical music to the simple chord progressions of modern pop.