Chord Progressions

Mastering the art of writing a pop song can feel like a daunting task, almost as if it’s a mystery known only to seasoned songwriters and producers. But, like any intricate recipe, once you understand the essential ingredients of a hit song, breaking down its structure becomes much easier. Strip away the advanced production techniques and sparkling vocals, and you’ll see that many pop songs rely on similar structures, melodic hooks, and chord progressions.

In this guide, we’ll focus on some of the most popular chord progressions commonly found in pop music. These chords are instantly recognizable, and once you get the hang of them, plus add a touch of creativity, you’ll be able to craft your own catchy tunes.

For those looking for inspiration with chords, Native Instruments products offer a wide variety of pre-set chord patterns to get started. For instance, MASCHINE’s Chord Mode provides an easy way to explore interesting harmonic sequences. Many Native Instruments tools come equipped with ready-to-use chords and riffs, making it easy to dive right in. Whether you’re looking for guitar-based progressions, keyboard harmonies, or string arrangements, you’ll find the right chords and motifs to spark ideas for your song.

In our audio examples, we used IGNITION KEYS, but you can easily join in by using your own instruments or some free music-making tools mentioned in Max Tundra’s pop music toolkit.

What Are Chord Progressions?

A chord progression, or harmonic sequence, is a series of chords that creates harmony and serves as the foundation for a melody. In Western music, chord progressions have played a key role since the classical era, continuing through to the present day as an essential part of popular genres like pop, rock, jazz, and blues. In these styles, chord progressions help define the character and sound of a piece, supporting its melodic and rhythmic elements.

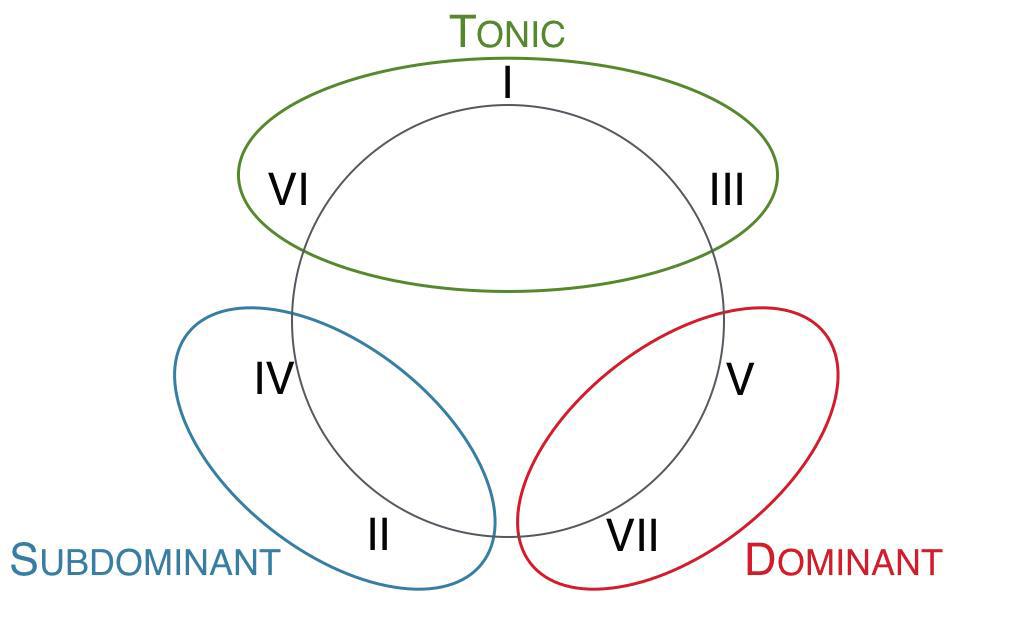

In tonal music, chord progressions help establish the key, or tonality, of a piece. For example, one common progression, like IV-vi-IV, is typically notated in Roman numerals in classical music theory, which allows musicians to recognize each chord’s function regardless of key. In popular music, these progressions are often named by chord labels alone. For instance, the same progression in the key of E♭ major would be written as E♭ major – B♭ major – C minor – A♭ major.

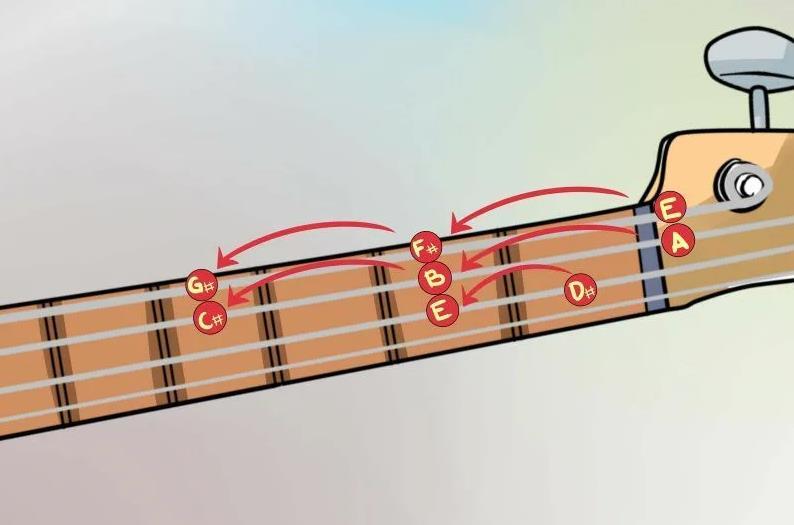

In rock and blues, musicians also often use Roman numerals to denote chord progressions, making it easier to transpose a song into any key. For instance, a 12-bar blues progression is usually built around the I, IV, and V chords, making it easy for a rhythm section or band to shift to the desired key on command. If the bandleader calls for this progression in the key of B♭ major, the chords would go: B♭ – B♭ – B♭ – B♭, E♭ – E♭ – B♭ – B♭, F – E♭ – B♭ – B♭.

The complexity of chord progressions varies by genre and era. Many pop and rock songs from the late 20th and early 21st centuries are built on relatively simple progressions, while jazz, especially bebop, often includes much more complex progressions, sometimes featuring up to 32 bars with multiple chord changes per bar. In contrast, funk is more groove- and rhythm-oriented, often revolving around a single chord throughout an entire piece, emphasizing rhythm over harmony.

Before You Start: Get Familiar with Chord Basics

Before diving into creating chord progressions, it’s essential to understand what chords are. A chord is a combination of three or more notes from a particular scale, played together to create a harmonious sound. Chords are named based on their root note and type, like major, minor, or seventh. For example, a C Major chord consists of the notes C, E, and G. When we talk about chord progressions, we mean a sequence of different chords played one after another. These progressions are often represented by Roman numerals, which indicate the intervals between chords and their relationship to each other. If you need a refresher on music theory basics, feel free to check out our guide on chord and harmony fundamentals.

Don’t worry if this all sounds a bit technical — we’ll be referencing well-known pop songs to help you hear these chords in action. We also recommend using Hooktheory and its TheoryTab database, where you can see chord visuals for popular songs and listen to them at the same time.

I IV V (1 4 5) Progression

The I IV V progression is one of the most recognizable. Even if you don’t know any music theory, you’ve probably heard it in songs like Ritchie Valens’ La Bamba (1958), Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone (1965), or the Ramones’ Blitzkrieg Bop (1976). This pattern is built around three major chords and creates a bright, energetic sound. Once you master the two types of barre chords on the guitar, you can easily play thousands of songs based on this progression. It’s suitable for rock, pop, country, and many other genres.

I V vi IV (1 5 6 4) Progression

This progression is known as the “four magic chords” because it appears in so many hits. It is the basis of Jason Mraz’s I’m Yours, Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey, The Beatles’ Let It Be, Bob Marley’s No Woman No Cry, U2’s With or Without You, Lady Gaga’s Poker Face, and dozens of other compositions. Its popularity is explained by its balanced sound, which is suitable for both lyrical ballads and rhythmic pop songs. If you want to see for yourself how versatile this progression is, watch the famous video Four Chords by Axis of Awesome – it contains dozens of songs built on this sequence.

vi IV IV Progression

This progression is similar to I V vi IV, but it starts with a minor chord, making it sound more melancholic. This order of notes changes the perception of the melody, creating a softer and more emotional atmosphere. This scheme can be found in such famous compositions as Africa by Toto and Boulevard of Broken Dreams by Green Day. Due to its expressive nature, it is great for ballads and lyrical songs.

ii V I Progression (2 5 1)

This chord progression is popular in jazz and is often used as a harmonic basis for many standards. It can be found in Take the A Train by Duke Ellington and Softly, as in a Morning Sunrise, which was performed by musicians such as John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. The ii V I progression serves as a kind of bridge back to the tonic chord, but in some songs, such as Sunday Morning by Maroon 5, it becomes the basis of the entire composition.

vi ii V I (6 2 5 1) Progression

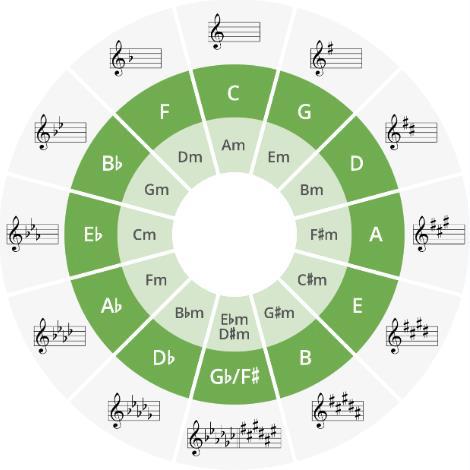

This pattern is based on the circle of fifths and creates a smooth, natural chord progression. It is called a “circular progression” and has been used in music for decades. One of the most famous examples is George Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm (1931). Seventy years later, the same pattern can be heard in Weezer’s Island in the Sun. This variation of the chord progression works well in both jazz arrangements and modern pop compositions.

Pachelbel Progression: How an Old Harmony Conquered Pop Music

Some chord progressions survive the ages, and the Pachelbel progression is one such example. It is built according to the pattern IV vi iii IV I IV V (1 5 6 2 4 1 4 5) and was popular long before the advent of modern music. Composer Johann Pachelbel first used it in Canon in D in the 18th century, but over time it migrated to dozens of pop hits.

This progression is not just used in songs – its melody is often literally repeated. One of the most striking examples is Memories by Maroon 5, where the motif is almost entirely based on Canon in D. In turn, Hook by Blues Traveller even mocks the stereotypes of modern pop compositions built on this progression.

Although the basic scheme remains unchanged, some bands have adapted it to their style. Green Day’s Basket Case and Aerosmith’s Cryin’ use the same basic structure, but instead of going back to the IV chord after the I, they go straight to the V, creating a more energetic sound.

The Pachelbel progression has become so common that it has spawned entire humorous videos. If you enjoyed Axis of Awesome’s Four Chords, you might want to check out Rob Paravonian’s Pachelbel Rant, a satirical medley about how the same musical pattern is repeated in countless songs.

Doo-Wop Progression: From the 50s to the Present

The I vi IV V (1 6 4 5) chord progression, known as the Doo-Wop progression, has become one of the most recognizable in popular music. It can be heard in compositions of various genres, from 50s classics to modern hits. These chords coincide with the so-called Axis Progression, but are arranged in a different order, which creates a characteristic soft sound, ideal for lyrical and romantic melodies.

One of the most famous tracks using this progression is Earth Angel by The Penguins (1954). The simple but expressive chord progression emphasizes the soulful vocal harmonies that became the hallmark of the Doo-Wop era. Another classic example is Heart and Soul, a popular piano duet that can be easily played on the white keys if you choose the key of C.

The simplicity of the progression does not prevent it from being used in a wide variety of genres. Elton John used it in Crocodile Rock (1972), conveying a nostalgic atmosphere of the 50s. In the 90s, it formed the basis of the indie-folk anthem In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Neutral Milk Hotel.

In the 21st century, the Doo-Wop progression is still in demand. Ed Sheeran used it in Perfect, DJ Khaled in I’m the One, Taylor Swift in Me!, and Daddy Yankee in Dura. Despite hundreds of songs built on this scheme, no one has yet put together a large-scale medley that unites all of these tracks, but interest in the progression does not fade.

Diatonic and Modal Chords: How Unexpected Harmonies Work

Most popular chord progressions are built on diatonic chords, that is, chords that belong to the same key. However, sometimes composers use modal alternating chords – harmonies that go beyond the expected structure. Such chords create the effect of surprise and give the melody a special mood.

One of the most common examples is the IV chord, which is often used to create a melancholic or even dramatic sound. It can be heard in Radiohead’s No Surprises – this chord plays a key role in the recognizable arpeggio in the intro.

The Beatles also used this technique extensively, especially on the album Rubber Soul. In In My Life, the IV chord helps emphasize the emotionality of the line “In my life, I loved you more”, and in Nowhere Man, it creates a special sound in the moment “Making all his nothing plans for nobody”.

Cadence ♭VI ♭VII I: Chords That Create a Feeling of Victory

Certain chord progressions evoke specific emotions in the listener, and the ♭VI ♭VII I cadence is one such example. It can be heard in video game soundtracks, especially in moments of triumph, such as after completing a difficult level. It creates the same sense of completion and solemnity in musical compositions.

This move is found not only in game soundtracks, but also in popular music. For example, in the song With a Little Help from My Friends by The Beatles, you can hear this harmonic device. Its peculiarity is that it gives the melody a powerful, confident sound, creating the effect of a triumphant finale.

Another interesting chord that affects the perception of music is ♭IImaj7. It is often used before returning to I to enhance the resolution and make the transition more expressive. This chord is especially popular in jazz, where it is used to create a slight delay before the main chord of the key.

Rock and alternative music also use this technique. For example, Radiohead’s Everything in Its Right Place and Pyramid Song borrow the ♭IImaj7 chord from the Phrygian mode, giving the songs a slightly dark and mysterious sound, even though they remain in a major key.

Chord Progression I III IV iv: The Creative Line Between Inspiration and Borrowing

Chord Progression I III IV iv: The Creative Line Between Inspiration and Borrowing

The Case of Radiohead and Lana Del Rey

One of the most famous cases involving the I III IV iv progression happened with Radiohead. Their hit Creep turned out to be too similar to the song The Air That I Breathe (1972) by Albert Hammond and Mike Hazelwood, which led to a lawsuit and the inclusion of the original authors among the copyright holders.

Years later, the situation repeated itself: Lana Del Rey used the same harmony in Get Free (2017), which led to a conflict with Radiohead’s publisher. Although the case did not go to court, the fact that the sequence was controversial highlights how important nuances in arrangement and melody are.

How to avoid being copied?

Chord progressions are just the foundation of a song, but to avoid being accused of copying, it is important to make other elements unique:

- Vary the rhythm and manner of performance;

- Create an original melodic line;

- Add non-standard arrangement solutions.