Guitar triads

Music is not only theory and terms. It is, first and foremost, a feeling. That is why when studying guitar triads, it is important not only to understand what they are, but also to learn to hear them in real compositions. Only then will the theory begin to come to life, and the knowledge will be useful in practice.

If you are just starting to understand chords, be sure to take the time to listen to how guitar triads sound in famous songs. For example, in Van Morrison’s “Brown Eyed Girl” the second guitar part is built on moving guitar triads. This is a great way to hear how chords work in context and support the melody. Thanks to this song, I myself first began to truly understand how chords are structured – perhaps it will help you look at them differently, too.

Do you like Dire Straits? In the composition So Far Away, the main riff is literally woven from different triad forms. Listening to it, you will be able to recognize how these chords create a recognizable sound and rhythmic structure.

And if you want to hear guitar triads used in a more aggressive manner, check out The Who’s “Substitute.” The main riff is built on the same grips we’ll be covering in this lesson, plus a few more that are a little more advanced.

How to Create a Guitar Triad: A Step-by-Step Explanation

Before you create a chord, decide what type of guitar triad you want to get – major or minor. This is not just a matter of taste: major chords sound light and open, minor ones – more tense and emotional. It all depends on what notes you choose.

The basis for building a guitar triad is the scale. For example, if you are building a major triad, take a major scale. In the case of a minor chord, use a minor one. It is the sequence of steps in these scales that helps to determine exactly what notes are needed.

A guitar triad always consists of three notes: the root, the third, and the fifth. This means that you first choose the root note – the one from which the chord will be built. Then you take the third: if the chord is major, this is a major third, if minor, a minor one. And finally, add the fifth – it remains pure in both major and minor.

Let’s look at an example. You want to build a major guitar triad from the note C. First, take the C major scale: C, D, E, F, G, A, B. In this scale, the first degree is C, the third is E, and the fifth is G. This means that the guitar triad will be C-E-G. This is the C major chord.

The algorithm for creating any guitar triad is as follows: choose the main note, determine the desired scale, find the first, third, and fifth degrees in it – and connect them.

What are guitar triads on the guitar and why do you need them?

Guitar triads are a great tool for any guitarist who wants to better understand music and navigate the fretboard. They are simple in structure, but very expressive chords made up of three different notes. And although the definition may sound simple, there is a clear logic behind triads based on intervals.

When we talk about guitar triads, it is important to understand that these are not just any three notes played at the same time. These are three specific steps of the scale: the root, the third, and the fifth. It all starts with choosing the root note – the root, from which the rest of the chord is built. Then a third is added – a major one for major triads or a minor one for minor ones – and finally a fifth, which is most often left pure.

Triads themselves come in four types: major, minor, diminished and augmented. Each of them has its own character – from a light and stable sound to a tense and unusual one. In addition to the type, it is important to understand that triads can be inverted. These are the so-called inversions – situations when the bass sounds not the tonic, but one of the other degrees.

In order to understand the construction of triads, you need to know a little about intervals – the distances between notes. Without this understanding, it will be difficult to assemble a chord consciously. For example, a major guitar triad is constructed like this: the tonic, a major third and a perfect fifth. This is the very “recipe” of a major chord.

Looking at the guitar neck, it is important not only to remember the fingerings, but to understand what notes each form consists of. Then you can freely move them along the neck, combine them and even create your own chord options. It all starts with guitar triads – a simple but powerful basis for chord playing.

A guitar triad is three notes with a certain distance between them. For example, from the root to a major third there are four frets, from the root to a perfect fifth there are seven.

Each type of chord has its own “recipe” of intervals. On the guitar, these intervals are easily measured in frets.

Let’s say you play the note C on the fifth fret of the third string. To get a major guitar triad, play E on the fifth fret of the second string (major third) and G on the eighth fret of the second (perfect fifth).

This is the basis: remember the distances between the notes – and you will be able to build any triads on the fretboard.

| Ingredient (Interval) | Guitar Frets (Semitones) |

|---|---|

| Root Note | 0 |

| Major Third | 4 |

| Perfect Fifth | 7 |

Let’s compare that to this quick analysis of a major guitar triad on the fretboard:

Let’s start with the base note. Let it be the fifth fret on the A string — the note A. We will build the rest of the chord sounds from it.

The next step is to find a major third. To do this, we will use the fourth fret on the D string. This is the note F♯, and it is located four semitones away from the note A — that’s how much is needed for the interval of a major third.

Now let’s add a perfect fifth. It is located on the second fret of the G string — this is the note E. It is separated from the note A by seven semitones, which makes it a fifth.

As a result, we get three notes: A, F♯ and E. This is a major guitar triad — the tonic, major third and fifth in one form on the fingerboard.

Triad of qualities

Earlier we looked at how a major guitar triad is structured. But the list doesn’t end there – there are four types of triads, and each of them has its own character and sound.

Here are the main types of guitar triads:

- major;

- minor;

- diminished;

- augmented.

Each type of guitar triad creates its own mood – and that’s why it’s so important to be able to distinguish and use them.

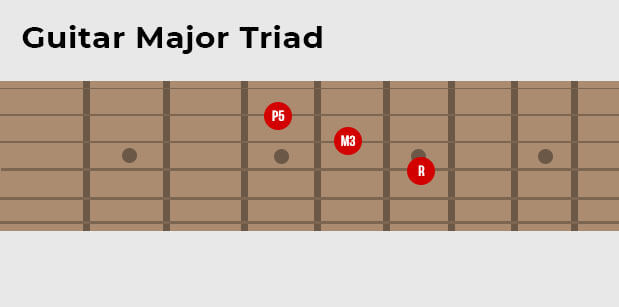

First, we have a major guitar triad, which we saw earlier. Its “recipe” is as follows:

| Major triad | |

|---|---|

| Root | R |

| Major third | M3 |

| Perfect fifth | P5 |

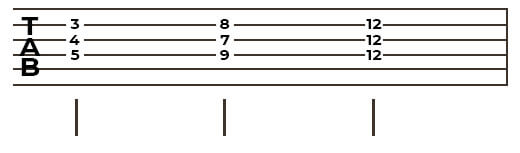

Here’s how we could play it on the fretboard:

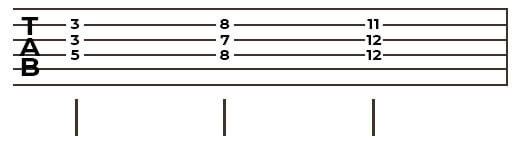

Next up, a minor guitar triad. All we have to do is change the major third to a minor third. Check it out.

| Minor guitar triad | R |

|---|---|

| Root | |

| Minor third | Minor third |

| Perfect fifth | P5 |

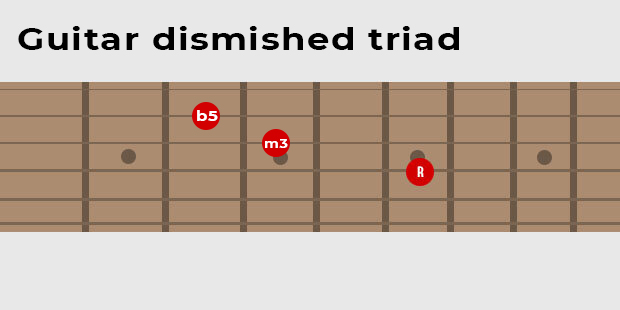

So, the major and minor guitar triads are definitely the most important. But we also have the diminished guitar triad. This is similar to the minor guitar triad, except we turn the perfect fifth into a diminished fifth.

| Diminished Triad | |

|---|---|

| Root | R |

| Minor Third | m3 |

| Diminished Fifth | d5 |

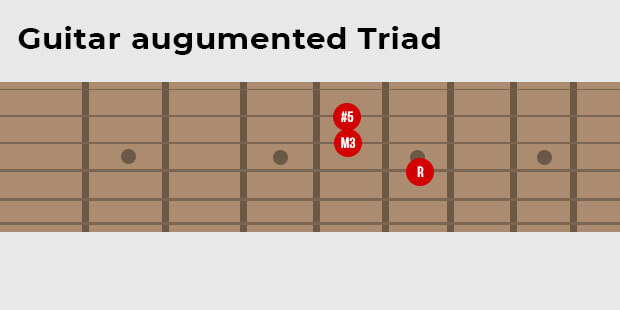

Finally, we have the augmented guitar triad. This is similar to the major triad, except we turn the perfect fifth into an augmented fifth.

| Augmented Triad | |

|---|---|

| Root | R |

| Major Third | M3 |

| Augmented Fifth | #5 |

Now you know all four types of guitar triads. Of these, major and minor are the most commonly used — they are the basis of most songs and chord progressions.

So in the next section, we’ll focus on them. We’ll look at how to play major and minor triads in different positions on the fretboard and how to change fingerings depending on the situation.

How to Use Guitar Triads for Guitar Improvisation

Guitar triads are great not only for accompaniment, but also for improvisation. For example, if someone plays a simple chord progression, you can add melodic moves based on triads to it – it sounds interesting and varied.

For the demonstration, I use a looper pedal and record the sequence C – G – Am – F. This is one of the most common options, and against its background you can freely move guitar triads along the fretboard, choosing the right positions within the key.

An important point: when you play triads, you do not need to touch all the strings, as with classical chords. It is better to extract each note separately – this way the sound will be clear, and you will be able to more accurately control the rhythm and accents.

Also try playing triads with short, abrupt chords. This can resemble funk or reggae. These phrases are easy to weave into a groove and add life to improvisation. Don’t be afraid to experiment – triads give you room for creativity even with a limited set of notes.

How to mute extra strings

If you play triads on the top three strings, the thick strings must be muffled. This is done with the inside of the palm of the right hand – the one that plays.

Sometimes you can additionally mute the fourth string with the finger of the left hand that holds the third. But the main thing is the right palm, and it should cover the bass strings.

Triad inversions: what are they and why are they needed

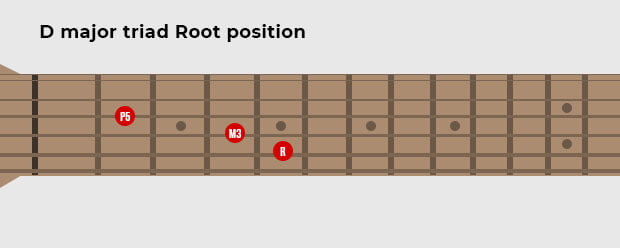

A guitar triad always consists of three notes: the root, the third, and the fifth. Usually they go in the usual order – first the root note, then the third, then the fifth. This is called the root position. But the order of these notes can be changed – this is how inversions appear.

There are three options:

- root position – the first note at the bottom is the tonic;

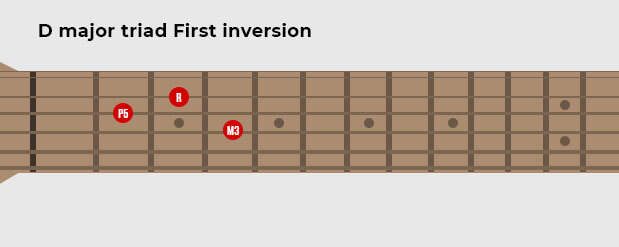

- first inversion – the third sounds at the bottom;

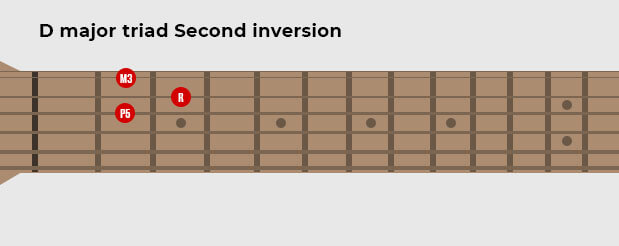

- second inversion – the fifth is in the bass.

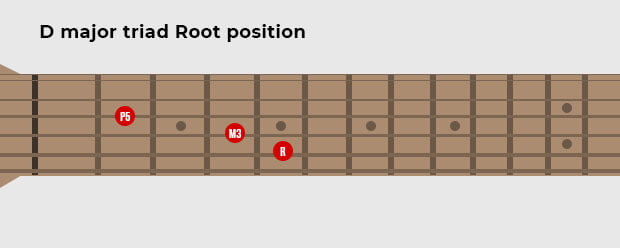

Up to this point, we have played chords in the root position. For example, the guitar triad D major consisted of the notes D, F♯ and A – in exactly this order. But if, say, you put F♯ in the bass – this is already the first inversion, and the sound becomes different.

Inversions are convenient for smooth transitions between chords and saving movement along the fretboard. Therefore, it is important not only to know them, but also to be able to use them.

To get the first inversion, we change the order to the third, fifth, root.

And for the second inversion we change the order to fifth, root, third.

Here’s a quick overview:

| Root Position | 1st Inversion | 2nd Inversion |

|---|---|---|

| R | M3 | P5 |

| M3 | P5 | R |

| P5 | R | M3 |

You may ask: why do we need inversions at all? The answer is simple – they open up more musical possibilities.

Firstly, each inversion has its own shade of sound. The main position sounds stable and familiar. But the first and second inversions sound softer, lighter, as if hanging in the air – especially if you play them in the high registers.

Secondly, inversions allow you to play the same chord in different parts of the fretboard. This is convenient when you need to make transitions between chords smoother and minimize hand movement.

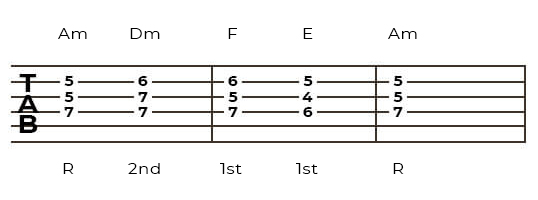

For example, take the guitar triad G major. It can be played in three different forms without leaving the key – just by changing the order of the notes. The same goes for G minor – the notes remain the same, but their arrangement changes, and with it the overall sound.

In practice, this is especially useful when the progression involves different chords. Let’s say you’re playing Am–Dm–F–E. With inversions, the notes on each string only move a couple of frets—there are no sharp jumps, and everything sounds smooth.

Try it yourself. Take, for example, a pair of chords – Am and F – and try to move between them using inversions. You will be surprised how new they can sound.

What comes next: seventh and ninth chords

Guitar triads are the foundation, but the language of music doesn’t end there. There are many chords that add extra notes. Some of the most common are chords with a seventh and ninth degree.

Seventh chords are built on the basis of a regular guitar triad and are supplemented by the seventh degree of the scale. Depending on whether this seventh is minor or major, we get different options: major, minor, or dominant seventh chords.

Ninth chords go even further. A ninth degree is added to the basic guitar triad and seventh. Such constructions sound rich and are often found in jazz, fusion, and soul. They add depth to the harmony and allow for more expressive arrangements.

Answers to frequently asked questions about triads

What is considered an example of a triad?

Any chord made up of three different notes. For example, C major (C–E–G), A minor (A–C–E), D diminished (D–F–Ab), or E augmented (E–G♯–C).

What does a “triad” mean in music?

It’s a chord made up of three steps: the root, the third, and the fifth. Triads are the foundation of Western harmony and are used in almost every genre of music.

What are the most common types of three-note chords?

Major, minor, and diminished. They are distinguished by the type of third and fifth they contain.

Now that you understand the essence of triads, you can not only recognize them, but also use them consciously. Apply this knowledge to your tracks and improvisations – and let the theory immediately come into play.