Triads in music

We can talk for a long time about what exactly is at the heart of music — the physics of sound waves, notes, the peculiarities of hearing. All of this really plays a role. But if we talk about what forms the musical fabric, makes it meaningful and expressive, then triads occupy a key place here.

A triad in music is not just a combination of three sounds. It is a tool with which a composer or producer can create a mood, build harmony and set the direction of the entire musical idea. It is with triads in music that an understanding of how chords work, how they interact and how they can be used in an arrangement or improvisation begins.

Even if you do not play the piano or guitar, but work exclusively in a DAW, knowledge of triads in music will help you quickly find the right consonances, experiment with progressions and better control the sound of a track. This is not an abstract theory, but a practical skill that affects everything: from building a bass line to choosing the upper melody.

In this article we will try to understand what triads in music consist of, what types there are, and how to apply them in real work – not only from a theoretical point of view, but also taking into account the tasks of modern sound design and production.

What are triads?

A triad is a chord of three notes spaced a third apart. For example, if you take the note C, then E and G, you get a major triad.

Such chords are the basis of Western music. Their sound is stable, clear and easy to combine with other chords. Triads are used in classical music, pop music, electronic arrangements and even beats.

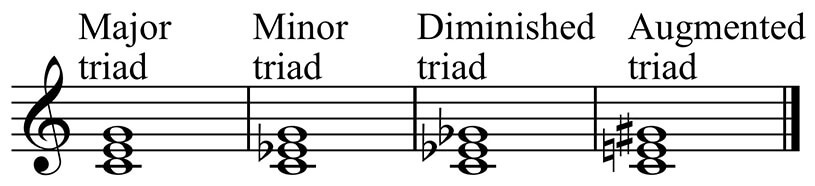

Types of triads

A triad in music is a harmonic combination of three sounds arranged in thirds. It is this arrangement that gives the sound stability and fullness. The main components of a triad are the root, third and fifth. Even if the chord is inverted and the first note is not the root, but, say, the third or fifth, it remains the same as the main tone – its function in harmony does not change. A triad in musical theory is formed as follows:

- Root — the initial tone from which the entire triad is built. It is what determines the name of the chord;

- Third — the second note of the triad, located at a distance of a minor (3 semitones) or major (4 semitones) third from the root;

- Fifth — the third note. The distance between the third and the fifth is also a minor or major third. Therefore, the fifth can be diminished (6 semitones from the root), pure (7 semitones) or augmented (8 semitones). The pure fifth is the most common option in classical, popular and folk Western music.

Modern View of Triads in Music Theory

In the 20th century, the concept of triads in music became broader. Music theorists like Howard Hanson, Carlton Gamer, and Joseph Schillinger proposed to consider any combination of three different pitches as a triad, regardless of the intervals between them. Schillinger, in particular, called such formations “structures in three-element harmony,” not necessarily corresponding to traditional diatonic chords. The term “trichord” is used to denote such extended forms of triads in music. Sometimes, one also speaks of “fourth triads” (based on fourth intervals) and “third triads” (made up of thirds).

The function of a triad in music

The main role in determining the function of a chord is played by its fundamental tone and its position within the tonality. The quality of the triad is also important – that is, whether it is major, minor, diminished or augmented.

In classical and popular music, major and minor triads are most often used. They can serve as a tonic – the main chord that sets the tonality. For example, a piece can be in the key of G major or E minor, but not in the key of C sharp diminished – such triads are used only as passing, temporary.

In the diatonic major scale, there are three types of triads in music theory: major, minor and diminished. Major and minor chords are considered stable and consonant, while diminished and augmented chords are unstable, requiring resolution. It is this difference that forms the character and movement of harmony in musical works.

How the Triad Became the Basis of Harmony in Western Music

The transition from complex polyphony to chordal thinking was one of the most important stages in the history of Western music. At the end of the Renaissance and especially during the Baroque period (approximately 1600–1750), musical style changed significantly. Instead of building a piece on several equal melodic lines, composers began to build a harmonic foundation using chords — primarily triads.

This shift was not just a stylistic decision, but a reflection of a change in the entire logic of music. The basis of accompaniment in the Baroque era was basso continuo — a numbered bass, where chords were built over a stable bass line. This practice required vertical (harmonic) thinking rather than horizontal (melodic). Triads in music became a convenient and universal support — they formed the foundation of what was later called functional harmony. The theoretical justification for the role of triads appeared as early as the 16th century. The Italian musicologist Gioseffo Zarlino was one of the first to draw attention to the importance of the triad in musical structure. And already at the beginning of the 17th century, the German theorist Johannes Lippius introduced the term “harmonic triad” in his treatise Synopsis musicae novae (1612), where he described it as the basis of musical structure.

How triads are built in music theory and what they consist of

Triads in music, like other chords built on the principle of thirds, are formed by superimposing every second note of the diatonic scale. For example, to get a C major chord, the notes C, E and G are taken – while D and F are omitted. This structure creates a triad of three sounds, where each subsequent one is located at a distance of a third from the previous one. However, it is important to take into account that thirds can be different – it is their combination that determines the type of triad in musical theory.

The main types of triads are built as follows:

- Major triad – a major third and a perfect fifth. In a semitone scale, this is 0-4-7. Example – C-E-G;

- Minor triad – a minor third and a perfect fifth. In semitone expression: 0-3-7. Example – A-C-E;

- Diminished triad — minor third and diminished fifth. Intervals: 0–3–6. Example: B–D–F;

- Augmented triad — major third and augmented fifth. Semitones: 0–4–8. Example: D–F♯–A♯.

If we consider the structure not from the root, but as a combination of two thirds, triads can be described as follows:

- Major triad — first a major third, then a minor third on top (for example, C–E–G: C–E is major, E–G is minor);

- Minor triad — first a minor third, then a major (A–C–E: A–C is minor, C–E is major);

- Diminished triad — two minor thirds one above the other (B–D–F);

- Augmented triad – two major thirds (D–F♯–A♯).

According to the arrangement of sounds, triads are divided into closed and open. In the closed position, all three notes are located next to each other, as close as possible to each other, within an octave. If the intervals between the voices are increased, and the notes are distributed more widely, then such a construction is called open position. This affects the overall sound of the chord and is used in the arrangement to achieve the desired timbre or density.

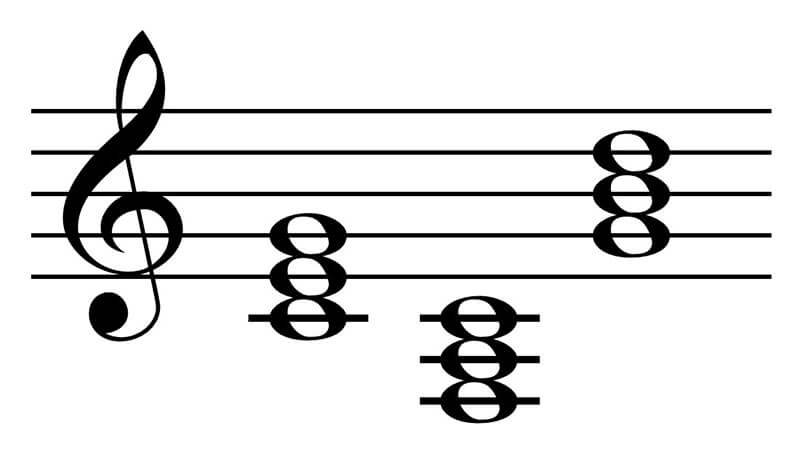

The functional role of triads in the diatonic system

Primary Triads in C

Within the diatonic tonality, each triad in music occupies its own specific place and performs a specific function. These functions follow from the position of the chord relative to the steps of the scale. The basis of harmonic organization is the system of functional harmony, in which chords do not simply sound, but perform a logical and expressive role in the musical phrase.

The main support of functional harmony is three primary triads. They are built on:

- the first step – the tonic (designated as I);

- the fourth step – the subdominant (IV);

- the fifth step – the dominant (V).

These chords form the “skeleton” of the tonality. The tonic triad creates a feeling of stability and completeness, the subdominant introduces tension, and the dominant reaches for resolution back to the tonic. Such interaction between functions underlies the overwhelming majority of harmonic sequences. In addition to the main trio, diatonics also uses auxiliary triads in music, built on other scale degrees:

- second degree — ii;

- third degree — iii;

- sixth degree — vi;

- seventh degree — vii° (diminished triad).

These chords do not play the main role, but complement and support the primary ones. For example, the ii chord often prepares the dominant, and vi can temporarily replace the tonic or enhance the feeling of major/minor coloring.

Classification of triads in music theory: by quality and by position

To describe triads more accurately, two main approaches are used – by the quality of intervals and by the position of the note in the bass. Both of these features help not only to name the chord, but also to understand its sound and role in harmony.

Quality of a triad in music theory. It depends on what intervals are formed between the three sounds of the chord. Depending on the combination of thirds and fifths, there are:

- major triads – contain a major third and a perfect fifth;

- minor – a minor third and a perfect fifth;

- diminished – a minor third and a diminished fifth;

- augmented – a major third and an augmented fifth.

These four types cover all possible combinations of thirds and fifths within the three-note structure.

The position of a triad in music theory. What is important here is not the composition of the triad, but which note sounds at the bottom:

- if the root (tonic) is in the bass, the chord is written in the root position;

- if the lowest note is a third, then this is the first inversion;

- if the fifth sounds at the bottom, this is the second inversion.

In any of these cases, the chord retains its harmonic essence – that is, its belonging to a certain degree, tonality and function. Only its sound distribution changes, which is important for arranging, leading voices or achieving a certain sound.

With all the changes – be it an inversion or a change in quality by a semitone up or down – the chord is still built on the same three degrees: the first, third and fifth. Even if one of the notes is raised or lowered, the letter structure is preserved. For example, in the triad A–C♯–E (A major) and in A–C–E (A minor), the notes are still arranged with a letter interval of one — A, C, E. This fundamentally distinguishes the triad from other types of chords, where new steps are added.

Major and minor triads in music: the difference in the third

Major and minor triads differ in only one note – the third. In a major triad it is major, in a minor triad it is minor. This change of one semitone affects the mood of the chord: major sounds bright, minor – softer and sadder. These two types of triads are most often found in songs and are usually the first to be mastered on instruments.

Major triads in music

Major triads are formed on the basis of the root, major third and perfect fifth. This combination gives the chord a bright, stable character. The sound of such triads is often associated with joy, clarity or solemnity.

For example, let’s take the B major triad. It is built from the note B, then two tones later – the note D♯ (a major third), and one and a half tones later – the note F♯ (a perfect fifth). The result is a chord of B–D♯–F♯. The B major triad sounds like this:

B major triad – several octaves

Here is a diagram of all the main triads:

| Key | Major Triad Composition |

|---|---|

| A major | A – C♯ – E |

| B♭ major | B♭ – D – F (or A♯ – C♯♯ – E♯) |

| B major | B – D♯ – F♯ |

| C major | C – E – G |

| D♭ major | D♭ – F – A♭ (or C♯ – E♯ – G♯) |

| D major | D major |

| E♭ major | E♭ – G – B♭ (or D♯ – F♯♯ – A♯) |

| E major | E – G♯ – B |

| F major | F – A – C |

| G♭ major | G♭ – B♭ – D♭ (or F♯ – A♯ – C♯) |

| G major | G – B – D |

| A♭ major | A♭ – C – E♭ (or G♯ – B♯ – D♯) |

Triads in brackets sound the same as the main ones, but are written differently. These are enharmonically equal chords. The choice of notation depends on the key: somewhere it is more convenient to use sharps, and somewhere – flats, so that the notes fit logically into the scale.

Minor triads in music theory: what they consist of and how they sound

A minor triad is formed from three notes: the tonic, a minor third, and a perfect fifth. Unlike a major triad, a minor third is used instead of a major third, which changes the emotional perception of the chord.

An example is the B minor chord. It is built from the notes B, D, and F♯. Between B and D there is one and a half tones (a minor third), between B and F♯ there are five tones (a perfect fifth).

Such a shift in the middle of the chord makes its sound less bright, slightly muffled, and often with a hint of sadness. It is the third that is responsible for this difference, and it is most often used to distinguish minor and major by ear. The triad sounds like this:

B minor triad – several octaves

Here is a diagram of all minor triads:

| Key | Minor Triad Composition |

|---|---|

| A minor | A – C – E |

| B♭ minor | B♭ – D♭ – F (or A♯ – C♯ – E♯) |

| B minor | B – D – F♯ |

| C minor | C – E♭ – G |

| D♭ minor | D♭ – F♭ – A♭ (or C♯ – E – G♯) |

| D minor | D – F – A |

| E♭ minor | E♭ – G♭ – B♭ (or D♯ – F♯ – A♯) |

| E minor | E – G – B |

| F minor | F – A♭ – C |

| G♭ minor | G♭ – B♭♭ – D♭ (or F♯ – A – C♯) |

| G minor | G – B♭ – D |

| A♭ minor | A♭ – C♭ – E♭ (or G♯ – B – D♯) |

Augmented and Diminished Triads: The Difference in the Fifth

Unlike major and minor chords, where the structure is stable and familiar to the ear, augmented and diminished triads differ precisely in the fifth — the third note of the chord. In the first case, the fifth is raised, in the second, it is lowered, and this creates a tense or unstable sound.

Augmented Triads

An augmented triad in music is built on the basis of a major, but with a raised fifth. For example, if you take a C major chord (C–E–G) and raise the G to G♯, you get C–E–G♯. Such a chord sounds tense and requires resolution — most often back to a stable chord, for example, to a major with a perfect fifth or a chord with a sixth.

These musical triads are rarely found in popular music, as they require careful handling. However, they are actively used in progressions where it is important to create a short-term sense of instability. One of the most striking examples is the work of The Beatles. Augmented chords can be heard in more than twenty of their songs, where they are used accurately and appropriately. The augmented fifth of our B major triad sounds like this:

Here is a diagram of all augmented triads:

| Key | Augmented Triad (with enharmonic notes) |

|---|---|

| A | A – C♯ – E♯ (same as F) |

| B♭ | B♭ – D – F♯ |

| B | B – D♯ – F♯♯ (same as G) |

| C | C – E – G♯ |

| D♭ | D♭ – F – A |

| D | D – F♯ – A♯ |

| E♭ | E♭ – G – B |

| E | E – G♯ – B♯ (same as C) |

| F | F – A – C♯ |

| G♭ | G♭ – B♭ – D |

| G | G – B – D♯ |

| A♭ | A♭ – C – E |

Complete enharmonic triads are not listed here – only notes of equal sound are given in brackets. This is necessary for orientation in different keys.

A diminished triad is formed on the basis of a minor triad, but with a lowered fifth. This means that two minor thirds in a row go up from the root. This construction makes the chord especially compressed in sound and gives it a sharp, alarming tone.

For example, the chord B–D–F consists of a minor third B–D and another one — D–F. The result is a sound that does not give a sense of stability and requires continuation. It is this tension that is actively used in harmony, especially in transitions and preparations for resolution.

Here is a diagram of all the diminished triads:

| Key | Diminished Triad (with enharmonic notes) |

|---|---|

| A | A – C – E♭ |

| A – C – E♭ | B♭ – D♭ – F♭ (same as E) |

| B | B – D – F |

| C | C – E♭ – G♭ |

| D♭ | D♭ – F♭ – A♭♭ (same as G) |

| D | D – F – A♭ |

| E♭ | E♭ – G♭ – B♭♭ (same as A) |

| E | E – G – B♭ |

| F | F – A♭ – C♭ |

| F♯ | F♯ – A – C |

| G | G – B♭ – D♭ |

| G♯ | G♯ – B – D |

Unlike the augmented triad, which is rare in natural scales, the diminished triad occurs naturally on the seventh degree of the major scale – as the basis of the vii° chord.

However, its use is not limited to this position. Composers often use diminished triads in other places, focusing on the movement of voices and the development of harmony. Such a chord can increase tension and lead to the desired chord with a characteristic sonic push.

Try to include a diminished triad when creating your own harmonic scheme – perhaps it will add the necessary sharpness and direction to the progression.

Triad Inversions

Earlier we looked at triads in music theory in their basic form – with the root below. This option is called the root position. But harmony becomes much more interesting when the order of notes changes, especially in the lower voice.

If a third is used as a bass, this is already the first inversion. For example, in a B major chord, the role of the bass can be played by D♯. Then such a chord is written as B/D♯ – indicating that D♯ sounds lower than the others.

When the fifth is below, we have the second inversion. For the same B major, this will be F♯ in the bass, and the chord designation will take the form B/F♯.

Inversions do not change the composition of the chord, but they greatly affect the sound and perception, especially in the context of the melody and bass line. This is why they are actively used in both classical and modern music.

Unlike major and minor chords, inverting an augmented triad presents certain difficulties. Formally, it can, of course, be inverted – if you follow the intervals, it will still be the same chord with the same notes, but in a different order.

However, from a musical point of view, the situation is not so clear-cut. When inverting an augmented triad, intervals are formed that can be perceived as the structure of a completely different chord. This is due to the fact that such chords often include notes with alterations – for example, G♯ or B♯ – and they do not always fit into the standard key.

Because of this, an inverted augmented chord can sound unexpected and be difficult to fit into the overall harmonic progression. In addition, such inversions are difficult to formalize in musical notation, especially if the goal is to maintain a logical and readable notation for the performer.

Triads in training: scale exercises for playing and composing

Working with triads in music is not only theory, but also a powerful tool for developing performing and creative skills. Regular practice using chords helps improve coordination, accuracy and understanding of harmony. It is especially useful to build improvisations based on chord sounds – the root, third and fifth. This allows you not only to hit the key, but also to accurately emphasize the sound of each chord.

One of the universal ways to practice is to play triads on a major scale. First, choose a key. For example, start with the note B on the 7th fret of the sixth string of the guitar. Go through the scale several times in this position to consolidate it by ear and in your hands.

Then move on to the chords that naturally appear within this scale and build triads from them. You can play them both up and down the fretboard. This exercise is not only suitable for guitar – it can be adapted for any melodic instrument, including voice, synthesizer or brass.

For greater effectiveness, it is advisable to use a metronome. This can be a regular click track in your DAW if you do not have a physical metronome at hand. The main thing is to maintain a steady tempo and clear articulation so that each triad sounds clear and conscious.

All Triads in the B Major Scale, Played in 7th Position, Ascending and Descending in 3/4 Time

Once you are confident in playing the basic triad pattern, start speeding up. It is important not to just play the notes mechanically, but to engage your ear. Sing each note as you play, and try to anticipate the next one – especially if it is a major or minor third. This practice develops precision of perception and control over the instrument.

One interesting technique is to change the time signature in the exercise. For example, if the triads are played in triplets, try counting in 2/4 time. This will disrupt the usual rhythm and create a sense of displacement – over time you will get back into phase, and this will give a strong boost to the development of a sense of rhythm and the ability to hear internal divisions. This approach works great not only for the ear, but also for the perception of form in the game.

The same triads in 7th positions, in 2/4 time

When you play triad sequences, try to consciously shift your perception of the rhythm. Instead of feeling the downbeat as a clear boundary between chords, try counting differently – so that the accent is inside the triad, and not between them. This creates the illusion that the chords begin in unexpected places.

For example, instead of the usual “B – D♯ – F♯, E – G – B” start to perceive the notes as pairs: “D – D♯, F♯ – E, G – B”. In this case, you do not change the tempo or rearrange the notes – only the sense of direction and connections between the sounds changes. The intervals begin to be read not as clear three-note blocks, but as waves, sometimes ascending, sometimes descending.

This approach is a great way to go beyond the usual auditory perception. It helps to develop flexibility in thinking and playing. Try changing accents, breaking up triads in different ways, playing with direction – all this keeps you alert and prevents you from getting stuck in automatism. The essence of the exercise is in the constant shift in perspective, which makes you hear and play even the most familiar things anew.

Conclusion on triads in music theory

Triads are not just a theoretical basis, but a real instrument on which music is built. Their structure is clear, the logic is understandable, and it seems as if everything comes down to a formula. But music is not mathematics, and triads are not limitations, but a starting point.

Understanding these chords helps you navigate freely in harmony: you know where everything comes from, how it sounds, and where it can lead. But it is equally important to be able to feel the moment when it is worth deviating from the scheme. Sometimes it is the deviation from the usual triad that creates the necessary emotion or an unexpected turn.

If you have mastered the material and started to apply it in a game or composition, that is already great. And if, thanks to this knowledge, you start looking for non-standard solutions, then the theory has really worked.

FAQ: Triads in Music – The Building Blocks of Harmony

What is a triad in music, really?

A triad is a chord made up of three notes: the root, the third, and the fifth. Think of it as the core of most chords you hear—whether it’s a simple folk song or a full-blown symphony, triads are everywhere.

Why are triads so important?

Because they’re the foundation of Western harmony. Most chords, even the fancy ones with 7ths and 9ths, are built on triads. If you understand triads, you’ve got a solid grip on how music is put together.

What are the main types of triads?

There are four basic types:

- Major triad – bright and stable;

- Minor triad – a bit moodier;

- Diminished triad – tense and unresolved;

- Augmented triad – dreamy or unsettled;

- Each type has its own flavor and emotional vibe.

How do I build a triad?

Start with a root note. From there, count up a third (either major or minor), then add a fifth (perfect, diminished, or augmented). For example, a C major triad is C (root), E (major third), and G (perfect fifth).

Are triads only used in classical music?

Not at all. Triads are used in every genre—pop, rock, jazz, EDM, country, film scores—you name it. They’re universal tools that adapt to any style.

Can triads be inverted?

Absolutely. That’s when you rearrange the notes so the root isn’t the lowest pitch. First inversion puts the third in the bass, second inversion puts the fifth in the bass. Inversions help smooth out chord progressions and add variety.

What’s the difference between a triad and a chord?

All triads are chords, but not all chords are triads. Triads are three-note chords. Add more notes (like a seventh), and you’ve got extended chords. Triads are just the starting point.

How can I practice triads?

Play them in different keys on your instrument. Try building triads from every note in a scale. Listen to songs and try to identify which triads you hear. Training your ear is just as important as finger exercises.

Do I need to know music theory to use triads?

Not necessarily. Many musicians use them intuitively. But knowing the theory can help you understand what you’re playing, make better choices when writing, and communicate more easily with other musicians.

Any tips for using triads creatively?

Sure! Try stacking triads on top of each other for cool layered sounds. Use triads over different bass notes for fresh harmonies. Or break up the triad into arpeggios—great for melodic lines and riffs.