What is indie rock

Indie rock first took shape in the early 1980s across the UK, the US, and New Zealand. At the time, the term referred to music released by independent labels, but it soon came to represent a broader aesthetic — raw, experimental, and driven more by vision than by commercial formulas.

One of the genre’s earliest foundations was the “Dunedin sound” from New Zealand, with bands like The Chills and The Clean. In the US, college radio stations were instrumental in promoting artists like The Smiths and R.E.M., giving airtime to music that felt outside the mainstream. By the mid-’80s, indie rock had started to take shape as its own scene, boosted by the UK’s NME C86 compilation and the underground rise of bands like Sonic Youth and Dinosaur Jr. in the States.

The ’90s brought a wave of new subgenres:

- Slowcore, with its moody, drawn-out tempos;

- Midwest emo, known for its heartfelt lyrics;

- Slacker rock, marked by laid-back delivery and lo-fi aesthetics;

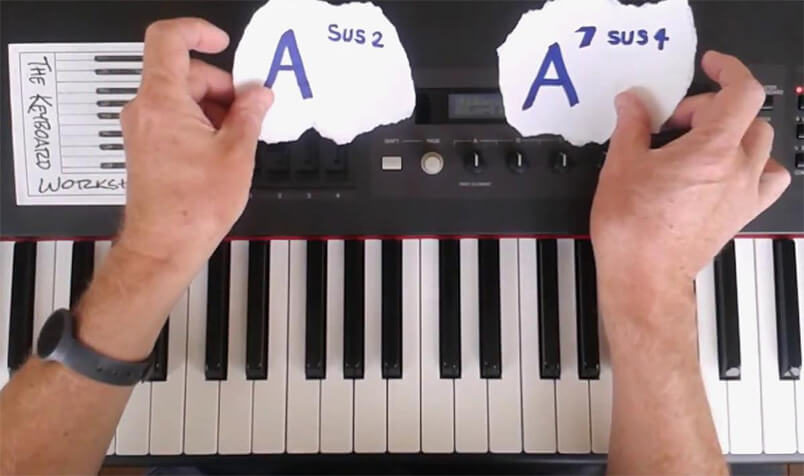

- Shoegaze, defined by heavy use of guitar effects and introspective vocals.

As grunge and Britpop gained momentum, the mainstream started co-opting indie sounds. Major labels leaned into the “indie image” as a marketing tool, which created a split: some bands leaned into the exposure, others doubled down on staying off the radar.

In the 2000s, indie rock made another leap into the spotlight. Acts like The Strokes, The Libertines, Arctic Monkeys, and The Killers brought a post-punk revival energy that connected with a new generation. That boom led to an explosion of similar-sounding bands — a wave the UK press later dubbed landfill indie.

Still, through all the shifts, indie rock has stayed true to its roots — centered on creative freedom, a DIY spirit, and an instinct to challenge the norm.

What Makes a Song Indie: Sound, Spirit, and Style

The term “indie” first emerged in the late 1970s in Manchester, when the band Buzzcocks released their EP Spiral Scratch without the help of a major label. That moment marked the start of a new kind of musical independence.

Indie isn’t just about who releases the music — it’s about creative control. Artists manage their own recording, direction, and sound without pressure from big industry players. This freedom leads to music that breaks away from formulas and feels more personal and original.

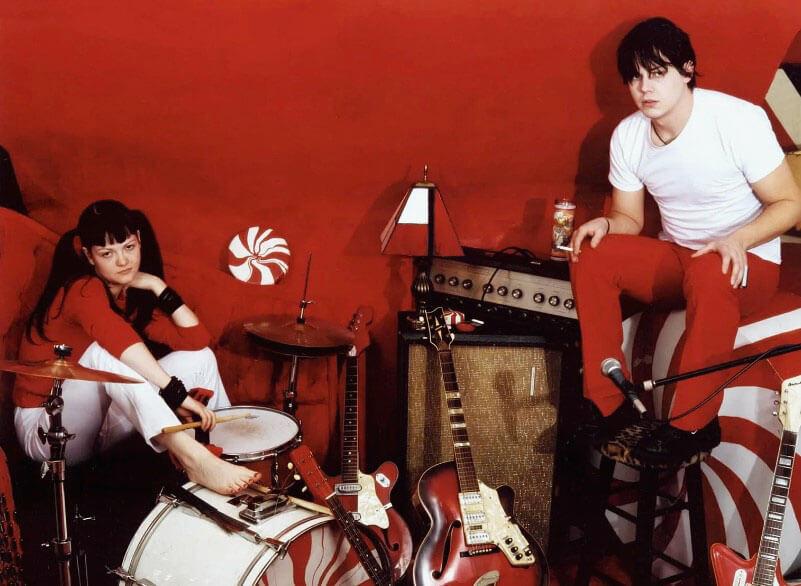

Stylistically, indie pulls from all over: punk, grunge, pop, hip-hop, even psych rock. That’s how you get bands like The White Stripes, blending garage rock with blues, or Young the Giant, who mix catchy hooks with layered guitar textures.

The White Stripes

Young the Giant

Even with all this variety, indie music still carries a recognizable energy. It’s raw, it’s honest, and it’s driven by the artist’s vision — not by trends or commercial charts.

Defining Traits of Indie Rock: Sound, Vision, and Contrast

Indie rock is more than just a genre — it’s a mindset, a way of making and sharing music. The word “indie” comes from “independent” and originally referred to artists and bands releasing music on small, low-budget labels. Even when distribution involved major companies, these artists aimed to preserve creative control and avoid being steered by industry trends.

That independence opened the door to experimentation — with sound, themes, and emotion — often far removed from what mainstream music was offering. Indie rock has always drawn from a variety of influences:

- punk and post-punk (Buzzcocks, Wire, Television);

- ’60s psychedelia and garage rock (Velvet Underground, The Doors);

- art rock and lo-fi aesthetics;

- touches of country and folk.

According to AllMusic, indie rock includes artists whose musical approaches often clash with mainstream tastes. It spans everything from guitar-heavy grunge to folk punk and avant-garde rock. What connects it all isn’t style — it’s a shared drive for autonomy and originality.

In his book, Brent Luvaas highlights how indie rock is rooted in nostalgia — for the sound of the ‘60s, for a DIY spirit, and for lyrics that often carry literary depth. That influence can be heard in bands like The Smiths and The Stone Roses, who emphasized both atmosphere and storytelling.

Musicologist Matthew Bannister once described the genre as “small groups of white guys with guitars,” drawing from punk and ‘60s rock, yet deliberately distancing themselves from commercial norms. Anthropologist Wendy Fonarow identified two major indie mindsets:

- the “purist” — favoring minimalism, rawness, and emotional honesty;

- the “romantic” — more expressive, eccentric, and stylistically bold.

This split was especially visible in the 1990s. UK bands leaned toward performance and aesthetic flair, while many American acts embraced a lo-fi, unpolished sound as a marker of authenticity.

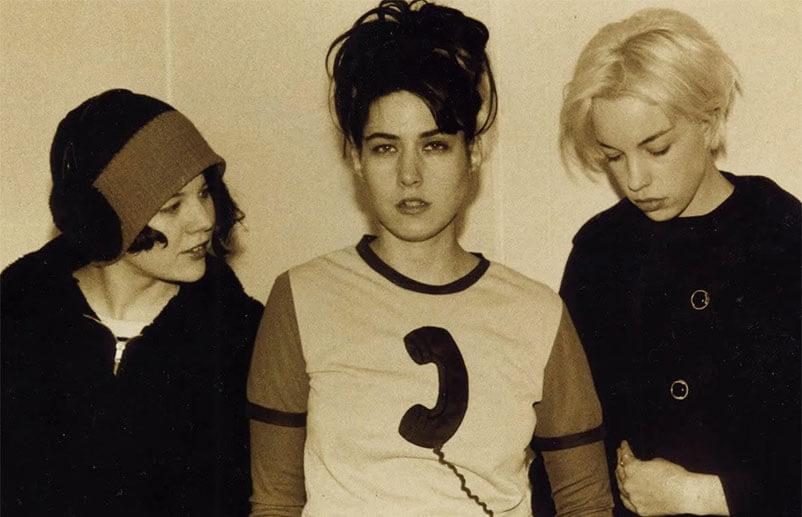

Indie rock also opened more space for women. The riot grrrl movement, led by bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Team Dresch, challenged norms not just by taking the stage, but by shaping the ideas behind the music. Still, as Courtney Harding notes, the same equality hasn’t extended to leadership — women running indie labels remain a minority even today.

Bikini Kill

Indie rock covers a wide range of styles — from synth-driven indie pop to raw post-punk and even hip-hop influences — but most indie bands share a few core values in how they approach music.

- DIY Ethos. Most indie artists operate outside the financial backing of major labels. They pay for studio time out of pocket or record at home with whatever gear they have. This hands-on approach keeps the process fully independent — from the first demo to the final release;

- Lo-Fi Aesthetic. Before software like Pro Tools and Logic became widely accessible, indie musicians often couldn’t afford professional studios. That gave rise to a recognizable lo-fi sound — gritty guitars, background noise, and an intentionally rough finish. Even today, some artists stick to that texture on purpose, using imperfections as part of their artistic identity;

- In-House Songwriting. Unlike pop or mainstream hip-hop, where songs are often built by teams of producers and writers, indie music is typically written by the artists themselves. That could mean solo singer-songwriters like Phoebe Bridgers, or full bands like Fugazi or Sleater-Kinney, where songwriting is a group effort — not outsourced to professionals;

- Authenticity Over Flash. Indie rock isn’t about shredding solos or vocal acrobatics. It leans into honest, human performances. Many indie bands can easily replicate their recorded sound live without needing a backup team of studio musicians — and that raw, unfiltered delivery is exactly what fans connect with. It’s less about perfection and more about real emotion.

How the Indie Rock Scene Began: From Buzzcocks to the Dunedin Sound

The BBC documentary Music for Misfits: The Story of Indie credits the origin of the term “indie” to the 1977 release of Spiral Scratch, a self-funded EP by Manchester punk band Buzzcocks, issued through their own label New Hormones. This move sparked a wave of DIY activity — bands began recording, printing, and distributing their own music. Groups like Swell Maps, ‘O’ Level, Television Personalities, and Desperate Bicycles soon followed.

Buzzcocks

Distribution grew with the help of The Cartel, a network of small distributors like Red Rhino and Rough Trade Records, which helped get indie releases into record stores across the UK. This infrastructure gave independent music a physical presence in shops, allowing it to compete with major-label releases.

Indie labels were also making waves outside the UK. In the U.S., Beserkley Records released the debut album by The Modern Lovers, and Stiff Records put out New Rose by The Damned, considered the first British punk single. In Australia, The Saints released (I’m) Stranded through their own label Fatal Records, followed by The Go-Betweens, who debuted with the indie single Lee Remick.

A key chapter in indie’s development unfolded in Dunedin, New Zealand. In the early ’80s, Flying Nun Records was founded, becoming home to a generation of artists who crafted what came to be known as the Dunedin Sound. According to Audioculture, one of the earliest bands in this scene was The Enemy, formed by Chris Knox and Alek Bathgate. Though short-lived, the band left a lasting impression on younger musicians like Shayne Carter, who went on to form DoubleHappys and Straitjacket Fits.

After The Enemy split, Knox went on to form Toy Love, and later Tall Dwarfs, one of the first acts to embrace home recording and lo-fi aesthetics — key elements in what would become the indie sound.

The Dunedin sound was marked by jangly guitars, subdued vocals, and a melancholic vibe. It gained wider recognition through The Clean’s 1981 single Tally-Ho! and the 1982 compilation Dunedin Double, which featured The Chills, Sneaky Feelings, The Verlaines, and The Stones. The style soon spread beyond Dunedin to cities like Christchurch and Auckland, helping shape indie rock as a distinct cultural movement.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., college radio stations became crucial for emerging independent music in the 1980s. They aired alternative rock, post-punk, post-hardcore, and new wave — sounds rarely heard on commercial radio. These bands were collectively referred to as college rock, a term tied more to the platform than to any single genre.

Artists like R.E.M. and The Smiths were especially influential. Musicologist Matthew Bannister considers them some of the first true indie bands. Their influence can be heard in groups like Let’s Active, The Housemartins, and The La’s. Around this time, the term “indie rock” began applying not just to labels but to the artists releasing music independently.

Journalist Steve Taylor also pointed to the Paisley Underground scene as an early part of the indie story. The genre grew darker and more atmospheric in the hands of artists like The Jesus and Mary Chain and Jean-Paul Sartre Experience, both associated with Flying Nun.

Eventually, after lobbying efforts by NPR led to a reduction in the number of college radio stations, the term “college rock” began to fade. In its place, a more flexible and lasting label took hold — indie — which would go on to define a generation of music that prioritized creativity, independence, and self-direction.

Jesus and Mary Chain

The Evolution of Indie Rock: From C86 to Grebo and Shoegaze

In the UK, a key turning point for the indie scene came with the release of C86, a compilation cassette put together by NME in 1986. It featured tracks from Primal Scream, The Pastels, The Wedding Present, and others who blended jangle pop, post-punk, and Phil Spector-style “Wall of Sound” production. Later, critic Bob Stanley called it “the beginning of indie music.” The term C86 quickly grew beyond the cassette itself, becoming shorthand for an entire wave of bands with breezy, lo-fi sounds — often labeled anorak pop or shambling indie. While some acts like Soup Dragons, Primal Scream, and The Wedding Present found chart success, many others faded into obscurity.

In the U.S., R.E.M.’s rise gave an alternative to the intensity of hardcore, opening the door for new musicians — particularly those who would go on to shape the post-hardcore scene, like Minutemen. Major labels took notice and briefly signed bands like Hüsker Dü and The Replacements, though their releases didn’t match R.E.M.’s commercial performance. Still, their influence was lasting. By the late ’80s, acts like Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr., and Unrest were releasing music through indie labels, and by the decade’s end, Sonic Youth and Pixies had signed to majors themselves.

Around this time, shoegaze emerged as a subgenre of indie rock, expanding on the “wall of sound” style pioneered by The Jesus and Mary Chain. Shoegaze fused that texture with elements from Dinosaur Jr. and Cocteau Twins, creating a dark, hazy atmosphere where instruments often blurred together. My Bloody Valentine were early pioneers with EPs and their debut Isn’t Anything, inspiring a new wave of bands from London and the Thames Valley like Chapterhouse, Moose, and Lush. In 1990, Melody Maker’s Steve Sutherland famously dubbed this scene “the scene that celebrates itself.”

Meanwhile, Madchester emerged as a hybrid of C86-style indie rock, dance music, and hedonistic rave culture, with heavy use of psychedelics. Based in Manchester and centered around the Haçienda nightclub — launched in 1982 by Factory Records — the movement drew energy from acts like New Order, Cabaret Voltaire, and The Smiths. By 1989, Happy Mondays’ Bummed and The Stone Roses’ debut had defined the scene. Acts like The Charlatans, 808 State, and Inspiral Carpets soon followed.

The Madchester sound — a mix of guitar-driven indie and danceable beats — became known as indie dance, or more specifically, the baggy subgenre. One of the movement’s defining moments was The Stone Roses’ Spike Island concert on May 27, 1990. With 28,000 fans and a 12-hour runtime, it was the first major event of its kind organized by an independent band.

At the same time, a distinct scene was growing in Stourbridge, known as grebo. Bands mixed punk, electronic, folk, and even hip-hop influences, crafting a heavier, dirtier sound. Led by Pop Will Eat Itself, The Wonder Stuff, and Ned’s Atomic Dustbin, the movement wasn’t so much a genre as a localized cultural moment. Their singles charted — Wise Up! Sucker and Can U Dig It? by Pop Will Eat Itself both landed in the UK Top 40 — and Stourbridge briefly became a pilgrimage site for indie fans.

Between 1989 and 1993, cornerstone albums of the grebo scene dropped: Hup and Never Loved Elvis from The Wonder Stuff; God Fodder and Are You Normal? from Ned’s Atomic Dustbin; and Pop Will Eat Itself’s This Is the Day… This Is the Hour… This Is This! and The Looks or the Lifestyle?. These bands became festival regulars at Reading, sold millions of records, and graced the covers of NME and Melody Maker.

What set grebo apart was not just its eclectic influences but its rejection of the polished or melancholic vibe that defined much of indie rock. It embraced distortion, swagger, and a tougher edge. Similar bands from nearby Leicester — Bomb Party, Gaye Bykers on Acid, Crazyhead, Hunters Club, and Scum Pups — soon became part of the movement, cementing grebo’s brief but loud place in indie history.

The Mainstream vs. Underground Split in Indie Rock: The 1990s

In the early 1990s, Seattle’s grunge scene exploded into the mainstream. Bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains became household names, with Nirvana’s breakout success drawing massive attention to indie rock. As a result, the term indie rock began to give way to alternative rock — a label that, over time, lost its original countercultural meaning. What was once associated with independence and outsider status became shorthand for a more commercially palatable version of guitar-driven rock that now topped the charts.

Carl Swanson, writing for New York Magazine, argued that even the term sellout started to lose meaning in this new landscape, as grunge proved that even the most niche or radical movements could be absorbed by the mainstream. What emerged was a fractured, individualist culture that still operated under the influence of major labels and media.

Media scholar Roy Shuker, in his book Popular Music: The Key Concepts, noted that grunge essentially became the mainstream version of the North American indie rock aesthetic of the ’80s. He suggested that being “independent” had, by then, become just as much of a marketing tool as any recognizable sonic trait. This shift caused a clear split in the indie rock world: some bands leaned into the accessibility of alternative rock radio, while others doubled down on experimentation and remained firmly underground. According to AllMusic, it was during this period that indie rock became more narrowly defined — referring specifically to the underground acts, while their more commercially successful peers were rebranded as alternative.

One of the clearest musical responses to this shift was slowcore, which developed in the U.S. as a direct contrast to grunge’s rising dominance. While the boundaries of slowcore are blurry, it typically features slow tempos, sparse instrumentation, and melancholic lyrics. Galaxie 500 — particularly their 1989 album On Fire — had a huge impact on the genre. As Robert Rubsam wrote for Bandcamp Daily, they were “the origin point for everything that came after.” The first wave of slowcore bands included Red House Painters, Codeine, Bedhead, Ida, and Low. The genre wasn’t tied to any one city or scene, and many of its artists developed in relative isolation from one another.

Around 1991, a younger, rougher offshoot of the grebo movement began to emerge. These bands were labeled fraggle — a name applied somewhat tongue-in-cheek to groups that drew heavily from punk, Nirvana’s Bleach, and often used drum machines. Stephen Klain of Gigwise described the sound as “dirty guitars, even dirtier hair, and T-shirts only a mom would wash.” Notable fraggle bands included Senseless Things, Mega City Four, and Carter the Unstoppable Sex Machine. They carried the indie spirit, but with a more chaotic energy and a visual style that was defiantly unpolished.

Senseless Things

Spin writer Charles Aaron described Pavement and Guided by Voices as “the two bands that defined indie rock during this era and, for many, still embody what the term means.” Both groups embraced lo-fi production styles that reflected and romanticized their DIY ethos. Pavement’s 1992 album Slanted and Enchanted became a cornerstone of the slacker rock subgenre. Rolling Stone called it “the quintessential indie rock album” and included it in their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.

In North Carolina’s Research Triangle, the indie scene was led by bands signed to Merge Records, including Superchunk, Archers of Loaf, and Polvo. These bands shaped a regional movement influenced by both hardcore punk and post-punk. Around that time, outlets like Entertainment Weekly were calling Chapel Hill “the next Seattle.” Superchunk’s single Slack Motherfucker was also spotlighted by Columbia Magazine as a defining anthem of ’90s indie rock and a symbol of the slacker stereotype.

Meanwhile, in the UK, the rise of Britpop pushed many early indie rock bands into the background. Led by Blur, Oasis, Pulp, and Suede, Britpop acts initially positioned themselves as underground alternatives — a response to the dominance of the American grunge scene. While Britpop owed much of its style to indie rock and began as part of that lineage, many bands rejected the genre’s early anti-establishment spirit. Instead, they brought indie firmly into the mainstream, with acts like Blur and Pulp signing to major labels.

In her essay Labouring the Point? The Politics of Britain in “New Britain”, academic and politician Rupa Huq argued that Britpop “began as an offshoot of Britain’s independent music scene but may have ultimately killed it, as indie and the mainstream converged — erasing the protest element that had once defined British indie music.” Music journalist John Harris traced Britpop’s origins to the spring of 1992, when Blur’s fourth single Popscene and Suede’s debut single The Drowners were released almost simultaneously. “If Britpop began anywhere,” he wrote, “it was in the wave of acclaim that greeted Suede’s early singles: bold, triumphant, and unmistakably British.” Suede was the first of a new wave of guitar-driven bands embraced by the UK music press as Britain’s answer to Seattle’s grunge. Their self-titled debut album became the fastest-selling debut in UK history at the time.

Diversifying Indie Rock

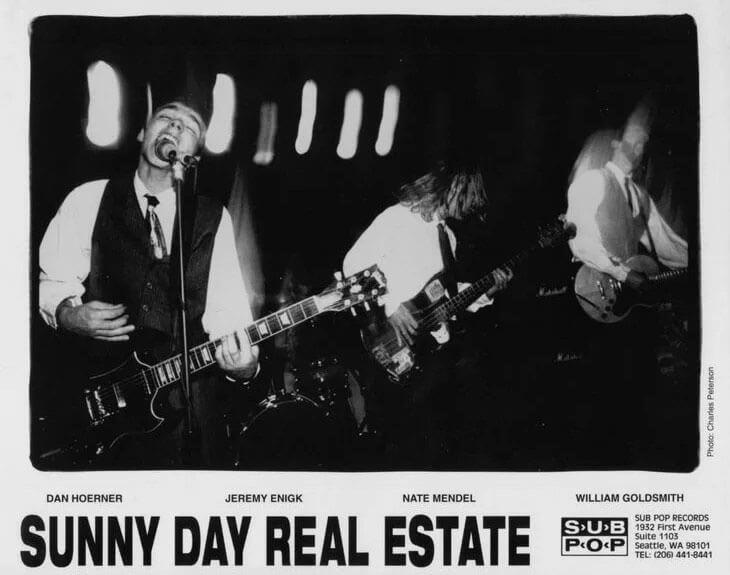

Sunny Day Real Estate’s debut album Diary (1994) helped usher in a new wave of emo by fusing emotional themes with indie rock aesthetics. Alongside bands like Piebald, The Promise Ring, and Cap’n Jazz, second-wave emo distanced itself from its hardcore roots, evolving into a more melodic and structurally refined genre.

This newer take on emo broke into the mainstream in the early 2000s with platinum-selling albums like Jimmy Eat World’s Bleed American (2001) and Dashboard Confessional’s The Places You Have Come to Fear the Most (2001). One particularly influential pocket of this movement emerged in the Midwest, where bands like American Football blended shimmering guitar tones and math rock elements into a distinct sound. Emo’s rising popularity also helped boost visibility for “in-between” acts like Death Cab for Cutie, Modest Mouse, and Karate — bands that didn’t fit squarely into emo or indie, but thrived somewhere in the overlap.

Meanwhile, the Elephant 6 collective — featuring Apples in Stereo, Beulah, Circulatory System, Elf Power, The Minders, Neutral Milk Hotel, and The Olivia Tremor Control — brought a psychedelic twist to indie rock. In Gimme Indie Rock, author Andrew Earles credited the collective — particularly Neutral Milk Hotel’s On Avery Island (1996) — with keeping indie artistically relevant during a period when other underground movements were beginning to fade or go mainstream.

Indietronica (or indie electronic) emerged as another fusion point, blending indie rock structures with electronic production — samplers, synths, drum machines, and software. Rather than a specific genre, indietronica described a broader movement in the early ’90s that drew on krautrock, synth-pop, and experimental traditions like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Foundational acts included the UK’s Disco Inferno, Stereolab, and Space, with most artists tied to labels like Warp, Morr Music, Sub Pop, or Ghostly International.

Space rock, another branch of indie, took inspiration from psychedelic rock, ambient textures, and the cosmic stylings of Pink Floyd and Hawkwind. Starting with Spacemen 3 in the ’80s, the style expanded through bands like Spiritualized, Flying Saucer Attack, Godspeed You! Black Emperor, and Quickspace, combining drone, atmosphere, and indie structure.

As Britpop faded in the late ’90s, post-Britpop carved out its own space within UK indie rock. Around 1997, disillusionment with Cool Britannia grew, and bands began distancing themselves from the Britpop label — even as they retained stylistic connections. With Britpop in decline, new bands gained broader critical and public recognition. The Verve’s Urban Hymns (1997) was a global hit and marked their commercial peak before splitting in 1999. Radiohead, meanwhile, had modest success with The Bends (1995) but broke through with OK Computer (1997), followed by the genre-defying Kid A (2000) and Amnesiac (2001), earning widespread acclaim.

Stereophonics mixed post-grunge and hardcore influences on albums like Word Gets Around (1997) and Performance and Cocktails (1999), before shifting toward more melodic songwriting on Just Enough Education to Perform (2001) and later releases.

Feeder, originally rooted in American post-grunge, found a heavier, more radio-friendly sound on their breakout single Buck Rogers and the album Echo Park (2001). Following the death of drummer Jon Lee, the band moved in a more introspective direction with Comfort in Sound (2002), which became their most commercially successful indie rock release, spawning a string of hit singles.

The most commercially dominant indie rock band of the new millennium was Coldplay, whose first two albums — Parachutes (2000) and A Rush of Blood to the Head (2002) — went multi-platinum, cementing their place as global superstars by the time X&Y dropped in 2005. Meanwhile, Snow Patrol’s Chasing Cars (from their 2006 album Eyes Open) became the most-played song on UK radio in the 21st century.

The Mainstream Rise of Indie Rock: The 2000s

The Post-Punk and Garage Rock Revival

Indie rock’s surge into the spotlight in the 2000s began with The Strokes and their 2001 debut album Is This It. Channeling the spirit of ’60s and ’70s bands like The Velvet Underground and The Ramones, the band aimed to sound, in their own words, like “a group from the past that traveled to the future to make a record.” While the album peaked at No. 33 in the U.S., it stayed on the charts for two years and debuted at No. 2 in the UK. At the time, mainstream rock was dominated by post-grunge, nu-metal, and rap-rock, making The Strokes’ raw, garage rock revival feel like a sharp contrast — and a breath of fresh air.

The band’s success helped shine a spotlight on other New York acts with vintage influences, including Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Interpol, and TV on the Radio. This garage-inspired wave also included The White Stripes, The Vines, and The Hives, who were quickly dubbed “The” bands by the media. Rolling Stone captured the moment with its September 2002 cover declaring, “Rock Is Back!”

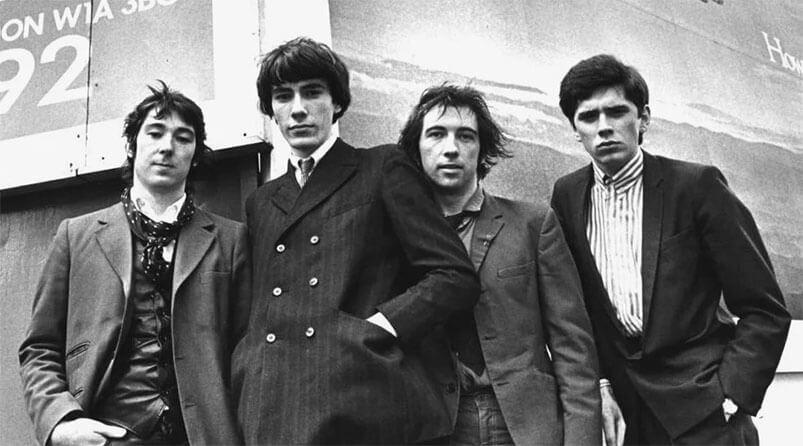

The momentum from The Strokes also sparked a revival in the UK’s fading post-Britpop underground. Inspired by their sound, a wave of British bands began reworking their approach. Early standouts included Franz Ferdinand, Kasabian, Maximo Park, The Cribs, Bloc Party, Kaiser Chiefs, and The Others. But The Libertines, formed in 1997, were seen as the UK’s direct answer to The Strokes. AllMusic described them as “one of the most influential British bands of the 21st century,” while The Independent noted, “The Libertines set out to be an important indie rock band, but couldn’t have predicted just how much they’d shape the scene.”

Blending influences from The Clash, The Kinks, The Smiths, and The Jam, The Libertines crafted a sound of tinny, trebly guitars and lyrics about British life, sung in unmistakably English accents. Their style quickly spread to bands like The Fratellis, The Kooks, and The View, all of whom found major commercial success. But no group made a bigger impact than Arctic Monkeys from Sheffield — one of the first bands to harness the power of social media to build a fanbase. Their 2006 debut Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not became the fastest-selling debut album in UK chart history, following two No. 1 singles.

This wave of popularity helped usher traditionally underground acts into the mainstream. Modest Mouse’s Good News for People Who Love Bad News (2004) broke into the U.S. top 40 and earned a Grammy nomination. Bright Eyes landed two No. 1 singles on the Billboard Hot 100 Single Sales chart in 2004. Death Cab for Cutie’s Plans (2005) debuted at No. 4 in the U.S., stayed on the Billboard chart for nearly a year, went platinum, and also earned a Grammy nod. With “indie” suddenly everywhere — from music to fashion and film — some critics began to argue the term had lost its meaning altogether.

Meanwhile, the U.S. saw a second wave of indie bands achieving global recognition. Groups like The Black Keys, Kings of Leon, The Shins, The Bravery, Spoon, The Hold Steady, and The National found both critical and commercial success. The biggest breakout of the bunch was The Killers, formed in Las Vegas in 2001. After hearing Is This It, they scrapped much of their early material and rewrote it with The Strokes’ influence in mind.

Their debut single Mr. Brightside became a phenomenon. As of April 2021, the track had spent 260 weeks (five years) on the UK Singles Chart — longer than any other song. By 2017, it had appeared on the chart 11 out of the previous 13 years, including a 35-week run that peaked at No. 49 during 2016–2017. Until late 2018, it was the most-streamed indie rock song in UK history and was still being downloaded hundreds of times per week as late as 2017. In March 2018, Mr. Brightside hit another milestone: 200 cumulative weeks in the UK Top 100.

The Spread of Indie Rock and the Rise of Landfill Indie

The success of bands like The Strokes, The Libertines, and Bloc Party sparked a wave of interest from major labels in the indie rock scene — a trend that only intensified following Arctic Monkeys’ breakout. In the years after the release of Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not, a flood of new bands emerged, including The Rifles, The Pigeon Detectives, and Milburn. Many of these acts offered a more formulaic, watered-down take on the sound of their predecessors.

By the end of the decade, critics began referring to this wave as “landfill indie” — a term coined by Word Magazine’s Andrew Harrison to describe the glut of indistinguishable guitar bands flooding the mainstream. In a 2020 Vice article, Razorlight frontman Johnny Borrell was dubbed “the one man who defined, embodied, and lived landfill indie.” Despite brushing up against the raw energy and mythic love-hate chaos of The Libertines, Razorlight was seen as emblematic of a band that embodied the surface, but not the soul, of the movement — “impressively average,” as the piece put it.

In a 2009 Guardian column, journalist Peter Robinson declared the landfill indie era officially dead. He singled out The Wombats, Scouting for Girls, and Joe Lean & the Jing Jang Jong as the final nails in the coffin. “If landfill indie were a game of Buckaroo,” he wrote, “these three would’ve sent the entire assload of radio-friendly monotony flying sky-high.”

Landfill indie ultimately became a symbol of how indie rock, once a rebellious alternative to the mainstream, had become saturated, commodified, and stripped of its edge.

Indie Rock’s Ongoing Success: 2010s to Present Day

The commercial success of indie rock carried well into the 2010s with major releases like Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs (2010), The Black Keys’ Turn Blue (2014), Kings of Leon’s Walls (2016), and The Killers’ Wonderful Wonderful (2017), which topped both the Billboard 200 in the U.S. and the Official Albums Chart in the UK. The Suburbs even took home the Grammy for Album of the Year in 2011. Other indie artists — Florence and the Machine, The Decemberists, and LCD Soundsystem — landed No. 1 singles in the U.S. during the decade, while bands like Vampire Weekend, Bon Iver, Death Cab for Cutie, The Postal Service, and Arctic Monkeys achieved platinum sales.

Vampire Weekend’s third album Modern Vampires of the City (2013) won the Grammy for Best Alternative Music Album in 2014, and in 2019, Consequence writer Tyler Clark described it as still “carrying the indie rock banner in the wider music world.” Arctic Monkeys’ AM (2013) became one of the biggest indie rock albums of the decade — debuting at No. 1 in the UK, selling 157,329 copies in its first week, and becoming the second-fastest-selling album of the year. With AM, the band became the first act on an independent label to debut at No. 1 in the UK with their first five albums. As of June 2019, AM had spent 300 weeks on the UK Albums Chart Top 100. The album also hit No. 1 in Australia, Belgium (Flanders), Croatia, Slovenia, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Portugal, and entered the Top 10 in several other countries.

In the U.S., AM sold 42,000 copies in its first week and debuted at No. 6 on the Billboard 200, becoming Arctic Monkeys’ highest-charting release in the States. By August 2017, the album was certified platinum by the RIAA, with over 1 million equivalent units sold in the U.S. As of April 14, 2023, every track on the album had been certified silver or higher by the BPI, with “Mad Sounds” being the last to reach that milestone.

Arcade Fire

In the early 2010s, The 1975 began merging indie rock with pop sensibilities — a move that initially polarized critics. They were named “Worst Band” at the 2014 NME Awards, but by 2017, they’d taken home the award for “Best Live Band.” Alternative Press’s Yasmine Summan wrote that if 2013 and 2014 could be summed up in a single album for fans of indie and alt music, it would be The 1975’s self-titled debut. In The Guardian, journalist Mark Beaumont credited the band with “ushering indie rock into the mainstream,” comparing frontman Matty Healy’s influence to that of Pete Doherty of The Libertines. Pitchfork also listed The 1975 as one of the most influential acts in music since 1995.

The band’s success helped spark a wave of similarly styled indie pop acts, a movement some critics dubbed “Healywave.” Notable names included Pale Waves, The Aces, Joan, Fickle Friends, and No Rome. Among them, Pale Waves stood out commercially. Their debut My Mind Makes Noises charted at No. 8 in the UK, Who Am I? (2021) hit No. 3, and Unwanted (2022) reached No. 4.

Around the same time, Wolf Alice emerged as a major force in the scene. Their second album Visions of a Life (2017) won the prestigious Mercury Prize in 2018, and their third, Blue Weekend (2021), was nominated. Writing for Dork in 2021, Martin Young noted, “It’s impossible to overstate how important Wolf Alice are. They’ve been the catalyst behind almost every brilliant band you’ve read about in Dork over the past five years.”

Iconic Indie Rock Albums and Songs

When Buzzcocks released Spiral Scratch in 1977, it became the first indie album in the modern sense. Initially pressed in a modest run of just 1,000 copies, the band and industry were shocked when demand forced them to print 15,000 more. The success of the EP marked the beginning of a growing community of artists committed to independence from the major label system.

Another landmark indie album was Pearl Jam’s Ten. Though more commonly associated with grunge, Ten played a major role in defining the sound of the 1990s Seattle scene and helped bring the term “grunge” into popular use. Like many indie and alternative releases of the time, the album was initially slow to gain traction, taking about a year to break into the Billboard charts.

Lyrically, indie rock has always leaned into storytelling — often deeply personal and emotionally resonant.

Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit captured the angst and confusion of youth under pressure.

Weezer’s Say It Ain’t So told the story of a family fractured by alcohol, inspired by frontman Rivers Cuomo’s childhood.

The Killers’ Mr. Brightside painted a vivid picture of jealousy and heartbreak — a man haunted by the thought of losing the one he loves to someone else.

These songs, with their raw emotion and sonic experimentation, helped shape the core of indie rock and continue to inspire new generations of musicians.

The Future of Indie Rock

As indie music becomes more accessible and mainstream, many believe the future of the music industry may lie in the hands of independent artists. With fewer gatekeepers, indie musicians are free to push boundaries, explore new sounds, and develop their own identities on their own terms.

Today’s new wave of artists is often described as genre-fluid — blurring the lines between rock, pop, hip-hop, and more. Artists like Dominic Fike and Declan McKenna represent this shift, crafting music that defies easy classification. As the music industry and its listeners become more diverse and open-minded, indie rock — in all its evolving forms — is poised to keep growing, shaping, and redefining what modern music can be.